Tughlaqabad Fort: Of a monarch and a revered Sufi

Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, the first ruler of the Tughlaq dynasty, chose the rocky site of Tughlaqabad to build the city so that it could be defended easily. It was built in four years but never fully populated and abandoned in 15 years.

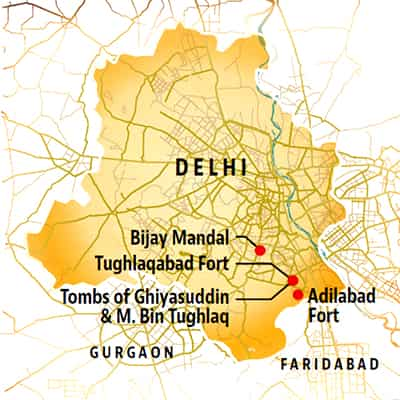

On the Mehrauli-Badarpur road, you cannot miss the grand Tughlaqabad Fort. Even in its state of ruin, the massive ramparts and bastions are humbling to passersby. The fortified city was the dream of Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, the first ruler of the Tughlaq dynasty that ruled from Delhi for almost a hundred years starting 1320 AD.

Military campaigns to consolidate power, attacks by marauding Mongols and reduced coffers marked the Tughlaq reign. Percival Spear, Delhi’s dogged historian, described the Tughlaq reign in his book, Delhi: A Historical Stretch, “It is a soldier’s age, stern and pitiless, and its spirit is reflected in its buildings, the unique and grim Tughlaq style.”

Both Tughlaqabad and Jahanpanah, the two fortifications left behind by the Tughlaqs, evince this emphasis on bolstering defences and dynastic pride. But looking beyond the flinty Tughlaq monuments tells us that cities are shaped less by kings, and more by the people they govern.

The saint and the sultan

Ghazi Malik, or Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, was the governor of Dipalpur in Punjab under Alauddin Khilji. When Khilji’s sons proved incapable of holding power, he orchestrated a coup and became the sultan.

Ghiyasuddin chose the rocky site for Tughlaqabad so it would be easy to defend. Work began on the fort, a massive, formidable structure with sloping walls.

It took four years to build the city of Tughlaqabad, but it was never fully populated, and merely fifteen years later, it was abandoned. Some say this was due to a shortage of water in the area. A spicier alternative offered by folklore suggests that Tughlaqabad was undone because of Ghiyasuddin’s hubris in picking a feud with 14th century Sufi saint Nizamuddin Auliya.

The story goes that Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq had made it mandatory for all the workers in Delhi to be employed in the construction of his fort. But at the same time, Nizamuddin Auliya was building a baoli (step-well), near the saint’s present-day dargah. By day, the city’s labourers worked on the fort; by night, on the baoli.

An angry Ghiyasuddin forbade the sale of oil to Nizamuddin, so no lamps could light up the construction site at night. The saint then magically turned the water in his tank to oil, and cursed Tughlaqabad: Ya base Gujar, ya rahe ujar (May this be inhabited by herdsmen or remain unoccupied).

Another folk tale adds to this narrative. Ghiyasuddin was in Bengal when he heard that defiant workers were working on Nizamuddin Auliya’s tank instead of the fort. The angry sultan vowed to punish the saint on his return.

When Nizamuddin Auliya heard of this, he came out with a portentous reply: Dilli hanuz dur ast (Delhi is yet far off). During the Sultan’s trip home, a pavilion erected on his behalf collapsed, killing him in the process.

The legend appeals to popular imagination, where an arrogant king is humbled by a pious saint. But the endurance of the myth also shows the influence that Nizaumuddin Auliya held back then, and continues to exert now.

“Historically, if you look at Delhi, it has developed around the places that Sufis lived,” says Sadia Dehalvi, who authored the book Sufi Courtyard: The Dargahs of Delhi. In Mehrauli, settlements grew around the dargah of Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, while present-day Chiragh Dilli and Nizamuddin Basti developed around the dargahs of the 14th century Sufi saints they are named after.

The influence of the Sufis shaped Delhi culturally, as the dargahs became centres for poets, travellers, musicians, philosophers. Even the kings did not remain untouched.

“The sultans have always stood at the court of the sufis, not the other way round,” says Dehalvi. “When Firoz Shah Tughlaq came to meet Naseeruddin Chirag Dehli, he waited like an ordinary citizen.”

Kings chose to be buried near the dargahs. Humayun’s tomb borders Nizamuddin’s dargah, while the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar wanted to be buried next to Bakhtiyar Kaki’s shrine.

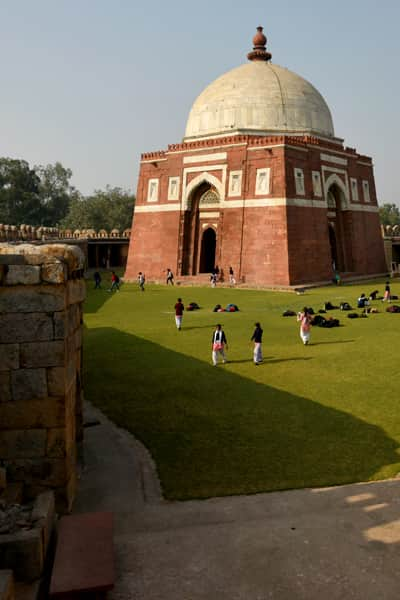

While Tughlaqabad lies in ruins, Nizaumddin’s dargah is one of the most venerated shrines in Delhi, thronged by the faithful. The baoli is still in use, fed by an underwater spring, and the waters are considered sacred. “These dargahs are not monuments, but living spaces, where people find refuge, compassion, this is the reason people go there,” says Dehalvi.

Uprooting a capital

Ghiyasuddin’s son,Muhammad Bin Tughlaq, took over the reins of the empire after his father’s sudden death. Muhammad bin Tughlaq built Adilabad, a small fort linked to Tughlaqabad through a causeway, which mirrored the bigger fort in style and substance.

As the Mongol threat grew, so did the sultan’s ambitions.

The old city in Mehrauli, by now, had expanded beyond the walls of Lal Kot. Khilji’s Siri was still fortified; Tughlaqabad was in decline, but still existed. So Muhammad fortified the area from Siri to Lal Kot — joining the three cities of Delhi — and called this enclosure Jahapanah (the refuge of the world). The remains of this city remains are well hidden in Khirki, beyond present day Press Enclave, but you can see some parts of its walls behind the Indian Institute of Technology and the Begumpur Masjid.

At Bijay Mandal, the palace Muhammad built within Jahanpanah, that lies in today’s Sarvapriya Vihar, you’ll see holes on the ground – these were for treasures, and rooms were the private chambers of the sultan.

It is said that like Siri, Bijay Mandal too had a Hall of Thousand Pillars, and you can see the sockets on the ground, where the pillars were fixed.

It was in this hall that 14th century Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta is said to have met Muhammad bin Tughlaq, after he arrived in Delhi in 1333. Battuta’s account of his time under the Sultan gives a glimpse into the splendour of Delhi, and then the scars wrought by uprooting the capital.

In 1327, Muhammad bin Tughlaq decided to shift the capital from Delhi to Devagiri (which he renamed Daulatabad), 1000 kilometres to the south. Battuta’s writings show how the whim of the sultan wreaked havoc on the city.

Battuta writes that Muhammad bin Tughlaq ordered his soldiers to search for anyone who had stayed behind in the city. His slaves found two men in the streets, a cripple and a blind man. The enraged sultan ordered the cripple to be flung from a catapult and the blind man to be dragged from Delhi to Daulatabad, a journey of forty days.

“He fell to pieces on the road and, of him all that reached Daulatabad was his leg,” wrote Battuta. “When the sultan did this, every person left the town, abandoning furniture and possessions, and the city remained utterly deserted… One night the sultan mounted to the roof of his palace and looked out over Delhi, there was neither fire nor smoke nor lamp, and he said, ‘Now my mind is tranquil and my wrath appeased’,” he writes.

Delhi didn’t remain abandoned, though. The sultan commanded the inhabitants of other cities to move to Delhi and eight years later, the capital was moved back. But neither the city nor its people could recover so easily from this uprooting.

Ziauddin Barani, the chronicler of Tughlaqs, writes in Tarikh-i-Firuz Shahi, that not many people returned, not even a “thousandth part” of the original population, and the city suffered. “Many, from the toils of the long journey, perished on the road, and those who arrived at Devagiri could not endure the pain of exile. They pined to death in despondency,” he writes.

An earlier version of the story said that Firoz Shah Tughlaq waited to meet Nizamuddin Auliya instead of Naseeruddin Chirag Dehli. The error has been corrected.