Wracked from within: In tribal Madhya Pradesh, TB continues to kill

There are families in these regions who are still losing as many as three members each as this curable disease spreads, unnoticed.

Boondi Adivasi, 23, is wild with grief. Her three-year-old baby girl Pinki died of acute malnutrition and tuberculosis (TB) at Shivapuri district hospital in Madhya Pradesh four weeks ago. She, however, is convinced a witch took her life.

“I saw a witch at home at 3 am and she took my baby girl at 3 pm,” Boondi says. “You killed her, taking her to the hospital killed her. I should have gone to the healer who drives away demons,” a suddenly angry Boondi tells her husband Suresh, as she grabs her year-old son Ganesh and storms away.

Her six-year-old son Manish and husband Suresh, 25, are also sick with TB, as is her newly widowed sister-in-law, Rumali, 25, who lost her husband Ramesh, 30, to TB in May.

Determined not to let anyone else in her family die, Boondi has travelled from her husband’s village in Jakhnod to the neighbouring Mahloni, where the faith healer Nandlal Adivasi, 80, has promised to heal her son for Rs 5,000, a sacrificial chicken and prayers to Ma Kali.

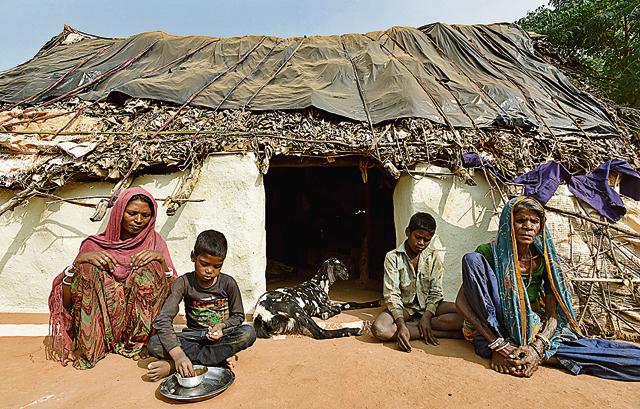

They belong to the Saharia tribe that has a population of 527,015 across Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, according to the 2011 census. Almost all work as farm labour on minimal wage or forage for honey and seeds in the forest.

They live in mud, stone and thatch homes with no toilets, relying on handpumps for drinking water.

“Boondi and I are the only [adults] not ill. She has to feed the children and fetch water, so I go out to earn to feed the family,” says Suresh’s widowed mother Baggo, 50, who earns between Rs 50 and Rs 150 a day collecting wild honey or working in the fields of affluent Yadav landowners.

On days when she doesn’t find work, the family of four adults and four children depends on the kindness of neighbours, or goes hungry.

MISERY HAS COMPANY

Theirs is not the only family in the village afflicted with tuberculosis. Dulari Adivasi, 50, and her daughter-in-law Santo, 40, both lost their husbands to TB. In September, Santo’s grandson Prahlad, 20, too succumbed to the bacterial infection, leaving behind his 18-year-old widow Rangvel and their two-year-old son, Giriraj. The three widows now live together and work as labourers to feed their children.

“My children are fine, they don’t cough,” says Santo, who works in the fields while her 14-year-old daughter Lakhmi looks after her brothers and nephew.

What she doesn’t know is that they may be infected with mycobacterium tuberculosis, the bacterium that causes TB.

People with latent TB infection do not have symptoms, but it may develop into full-blown disease — with symptoms of cough, weight loss, appetite loss and lowgrade fever — whenever their immunity takes a dive and their body can no longer fight the infection.

With malnourishment rife among the Saharias — deaths of children under 5 from acute malnutrition are not uncommon — TB stalks almost every home.

“Overcrowded huts with no ventilation or sanitation add to the problem, as do social determinants such as poverty and the back-breaking physical labour they do all day in the fields and stone quarries,” says Ajay Yadav, founder of the NGO Badlav (Hindi for Change).

Ajay has been working on health and nutrition with the Saharias for more than a decade. “Their malnourished bodies cannot bear the drug toxicities and sideeffects, so they stop,” he says. “Each family in this village has lost at least two or three people to TB, but when deaths happen at home, the causes are rarely recorded as TB.”

A FIGHT TO THE FINISH

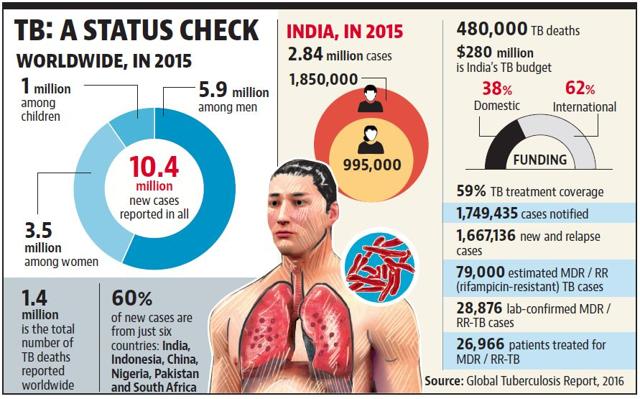

Of the 9.6 million TB cases worldwide, 2.2 million are in India, estimates the World Health Organisation’s Global TB Report, 2016. India’s Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) offers free diagnosis and treatment, including anti-TB drugs, to everyone, and designated microscopy centres have been established for quality diagnosis for every 1 lakh of the population in the general areas and for every 50,000 of the population in tribal, hilly and difficult areas.

Yet the services are not used by those who need them the most.

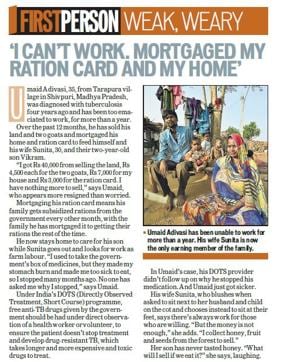

Though Suresh lost his brother to TB in May and is sick with TB himself, he does not take the free anti-TB drugs offered by the government because of the severe side-effects, which include fevers and stomach burn.

His son and widowed sister-in-law have also stopped taking their medicines, and have turned to faith-healers.

Under RNTCP, patients are given fixed-dose combinations of four medicines — isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol — for the initial two months, and three drugs — isoniazid, rifampicin and ethambutol — in the four months of follow-up, which can be extended to six months.

All patients have to take the TB medication for six to nine months to ensure they do not develop multidrug-resistant TB (MDR) and extremely drug-resistant TB (XDR TB), which have to be treated with very expensive and highly toxic medicines over two or more years.

“Drug toxicities in malnourished and immune-compromised patients is a challenge, as is rising resistance to anti-TB drugs, which the government is countering by using rapid molecular diagnostic by CBNAAT and use of the new anti-TB medicine bedaquiline through conditional access for MDR- TB,” said a Union health ministry officer, who does not want to be named. “People have to finish the full course of treatment, or the disease just comes back in a more potent form.”

The WHO’s End TB Strategy has three targets: lowering the incidence, the absolute number of TB deaths, and the percentage of patients and households that experience catastrophic costs because of the disease.

If India fails the Saharias, it will fail on all three counts.

Catch your daily dose of Fashion, Health, Festivals, Travel, Relationship, Recipe and all the other Latest Lifestyle News on Hindustan Times Website and APPs.