Mahadevi Varma: The poet who broke free, and inspired others to

In Women’s History Month, Poonam Saxena looks back on the extraordinary life of a revolutionary feminist and writer.

Years before Frenchwoman Simone de Beauvoir released her influential book, The Second Sex (1949), one of India’s early feminists, Hindi poet Mahadevi Varma, wrote a series of powerful essays on the oppression of women, for journals such as Chand, in the 1930s. Subsequently, the essays were collected in a volume called Shrinkhala ki Kadiyan (Links in the Chain), published in 1942.

As we progress into Women’s History Month, it’s a good time to remember the erudite and fearless Mahadevi, a rather stern-looking woman usually clad in plain white khadi saris with coloured borders (stern is how she looks in photographs, but she was apparently well-known for her full-throated laugh).

Even a bare-bones look at her life reveals Mahadevi’s astonishing independence and determination. Born in 1907 (though some scholars put her birth year at 1902) in Farrukhabad in Uttar Pradesh (UP), her father, a professor of English, was keen on his daughter getting an education, so Mahadevi studied at Crosthwaite Girls College in Allahabad, graduating in English, Hindi and philosophy. Later she got a postgraduate degree in Sanskrit.

As was the norm at the time, she was married early, at age nine, to a doctor, Swarup Narain Varma, and should have shifted to her husband’s home upon reaching puberty. But Mahadevi refused to set up house with him. The courage this called for at the time is hard to appreciate today; it is also remarkable that her parents didn’t force her hand.

Mahadevi never spoke about why she rejected the marriage; her husband also maintained a lifelong silence on the subject, even though he outlived her (she died in 1987). Neither of the two married again. Instead, Mahadevi went on to live a busy, creative life. She forged a career in education, first becoming dean of a women’s college in Allahabad in 1932 and later its principal.

I spoke to the very talented contemporary Hindi poet Anamika, who said of Mahadevi, “She created around her a ‘family of friends’. This is special to women writers – more than blood bonding, they create an adopted family of their own.” Mahadevi’s family consisted of the subalterns she befriended and wrote about all her life — marginalised people like Alopi the sightless vegetable seller; impoverished nine-year-old Ghisa, who had no books but a thirst for reading; Bhaktin the tormented widow, and many others.

Mahadevi was feted in her lifetime, winning almost every major literary award in India. Like the rest of the nation, she came under Mahatma Gandhi’s spell and fought for India’s freedom too, editing the revolutionary journal Chand at one point, helping distribute anti-British pamphlets (it is said she hid them in students’ lunch boxes) and sheltering freedom fighters in her home, often at great risk to herself.

She took a vow to always wear khadi and to never speak or write in English. Like the Mahatma, she famously never looked at herself in a mirror; it is said there were no mirrors in her home.

Mahadevi was the only woman in the group of four poets (the other three being Suryakant Tripathi Nirala, Jaishankar Prasad and Sumitranandan Pant) that founded a new romantic school of Hindi poetry called Chhayavad. This in itself was extraordinary, since most women at the time couldn’t read or write (the female literacy rate in UP in 1911 was 1%). The Hindi public sphere was not particularly generous to women writers either, Anamika says. In fact, after a bad experience at a kavi sammelan in Lucknow, Mahadevi took a vow never to recite her poems in public. She kept her word.

“Even today,” says Anamika, “audiences will comment on a woman poet’s voice, way of reciting the poem, not the poem itself.”

Mahadevi had a lifelong, close friendship with another great fellow poet, Subhadra Kumari Chauhan, whom she had known since their school days. Chhayavad co-founder Nirala was another dear friend, on whom she tied a rakhi every year.

A tall, striking man, the brilliant and mercurial Nirala faced crippling tragedies (he lost his father, wife and brother to an influenza epidemic, and his daughter died when she was just 18) and extended bouts of near-penury because of his disregard for money. Legend has it that he once arrived at Mahadevi’s house on Rakshabandan, but after she had tied on the rakhi and he had given her a little money as was customary, he promptly asked for it back since he wouldn’t otherwise have enough for the rickshaw ride home.

In her book Path ke Saathi (Fellow Wayfarers), Mahadevi painted vivid portraits of Chauhan and Nirala, among other writers.

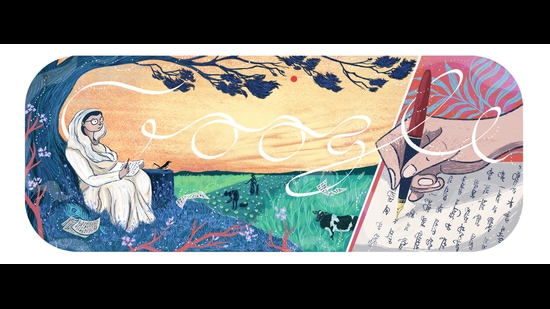

Often called an agni rekha, Mahadevi blazed a trail across the Hindi literary firmament. But she’s still relatively unknown outside the Hindi-speaking world. Google did a doodle on her in 2018, which, I suppose, was a start.

Catch your daily dose of Fashion, Health, Festivals, Travel, Relationship, Recipe and all the other Latest Lifestyle News on Hindustan Times Website and APPs.