Kashmir: A bold strategy isn’t always wise

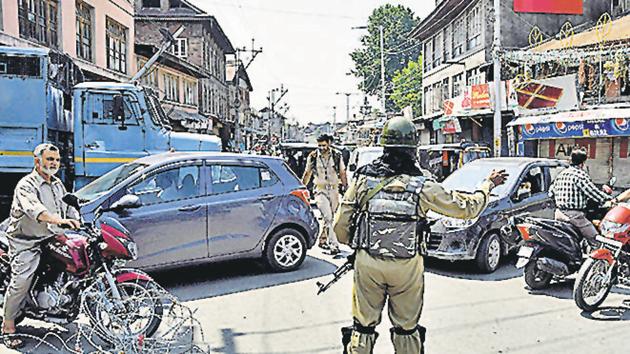

Centralisation, not autonomy, has driven revolts. Delhi’s Kashmir move could make matters worse.

Will revoking articles 370 and 35A bring peace to Kashmir? The government and its supporters have outlined their theory of the case. A new economic order will bring development, transforming the political preferences of Kashmiri Muslims toward India. Law and order will be removed from electoral politics because of Delhi’s control over security forces. The mainstream political parties will be tossed aside in favour of a new generation of Kashmiri loyalists who rise through local politics. As more non-Kashmiris move into the territory, its Muslim majority will fade. And by refusing to involve Pakistan, the government will firewall the internal dynamics of Kashmir from the regional context.

This is a bid to depoliticise Kashmir. The “big question” of Kashmir’s status, the government decrees, is no longer a big question, but instead a settled issue. There is nothing more to discuss, so Kashmiri Muslims should occupy themselves with development.

There are many ironies in this strategy. The first is that it flies in the face of decades of Delhi’s line. Having insisted that normalcy was soon returning to Kashmir, that only a marginal bloc of Kashmiri malcontents was causing trouble, and that sceptics were biased against India, the consensus has now pivoted to the position that seven decades of policy were a hopeless and obvious failure. If one isn’t careful, the switch from “normalcy is around the corner” to “this is an unsustainable disaster” could cause serious whiplash.

The second irony is the broad acceptance, by both proponents and opponents of Article 370, that reducing Kashmir’s autonomy in the past did not end well. The outbreak of insurgency in the late 1980s had key roots in the moves made by Delhi and its favoured political allies in the state to restrict Kashmiri autonomy. Indira Gandhi’s bid for centralised political control over the states in the 1980s and the rigged election of 1987 are widely seen as triggers for the outbreak of militancy, against a backdrop of central intervention from 1953. Security forces have had extensive freedom to act in Kashmir, with little accountability for credible allegations of human rights abuses.

Thus, much of the violence and political dysfunction that made Article 370 allegedly “unsustainable” were in fact results of government policy. It is not obvious that a more ambitious version of this strategy will have radically different results. If 370 was, at this point, mostly symbolic, then its revocation is unlikely to be a game changer. The record of other Indian states makes clear that corruption, inadequate development, discrimination, demands to economically favour local populations, and dynastic politics are not unique to those with special status.

Third, the game plan outlined by Amit Shah and Narendra Modi has striking similarities to past strategies. Previous governments have repeatedly invoked “development”: The 1950s and 1960s, for instance, saw huge infusions of central resources to build industry and economic growth in order to hold Sheikh Abdullah and his loyalists at bay.

Delhi has also long had local allies. It is fascinating to see the National Conference (NC) and Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) now being accused of being bastions of separatism, given their extensive history of junior partnership with Delhi. Indeed, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) allied with the PDP from 2015-2018, and even made development a core part of its message. The “new generation” of Kashmiri pro-India political mobilisation is likely to be an even more exaggerated version of the past – a reliance on localised patronage combined with deference to Delhi on key political questions.

The greatest irony is that this move flies in the face of what has worked to prevent and resolve conflicts elsewhere in India and South Asia. It is extremely rare for excessive autonomy to cause rebellion: Separatist revolts in Baluchistan, East Pakistan, the ethnic peripheries of Myanmar, Bangladesh’s Chittagong Hills Tract, and Tamil areas of Sri Lanka were instead driven by government centralisation. In India, both the Kashmir and Punjab insurgencies had roots in Indira Gandhi’s desire for control.

The Indian government has often recognised the dangers of inadequate autonomy. The linguistic reorganisation and compromises of the 1950s and 1960s were stunningly successful in avoiding the devastating ethno-linguistic conflicts that tore apart Pakistan and Sri Lanka. In the Northeast, states and autonomous districts have been created to foster more, rather than less, autonomy. Article 371A, regarding Nagaland, has not faced the same kinds of attacks as Article 370. Autonomy-enhancing bargains have, despite their flaws, been better than the alternative. During insurgencies in Punjab and Assam, the government sought to put local politicians front-and-centre who could consolidate support for Delhi.

Perhaps everything will be different in the New India. The government has enormous economic resources, security forces, and political support at its disposal. It is certainly possible that Delhi will achieve its goals in Kashmir. And there is undoubtedly important unfinished political business in Kashmir, even if my view of their sources and possible solutions - such as more creative and meaningful forms of autonomy — is different than the government’s.

Regardless of what the future holds, however, the gauzy and triumphalist language around the change in status avoids hard truths that any honest analysis of internal security in South Asia raises. There are good reasons to fear that this move will make things worse, not better. The government’s own lack of confidence is revealed by its detention of politicians and activists, and its decision to deny and attack press reports that inconveniently turn out to be true. Just because a strategy is bold does not mean it is wise.

Paul Staniland is associate professor of political science at the University of Chicago and author of Networks of Rebellion: Explaining Insurgent Cohesion and Collapse (Cornell, 2014).

The views expressed are personal