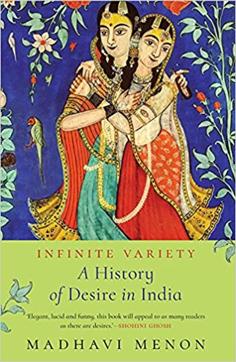

Excerpt: Infinite Variety; A History of Desire in India by Madhavi Menon

Hair has been a marker of sexual attractiveness in India across gender and religions. This edited excerpt looks at the history of hairy desire in the country

The fair one sleeps on the couch, with dark tresses all over her face;

Come, Khusro, go home now, for night has fallen over the world.

—Amir Khusro

The urbane young man at the heart of the Kamasutra is told early on in the book to take good care of his hair. This includes removing the hair from his body and maintaining well the hair on his head. Such a man would not be considered heterosexual today; instead he would be termed ‘metrosexual’ because he is not quite straight. His bodily hairlessness will be cause for suspicion because men are thought to be sexually virile if they have lots of hair on their bodies, and unmanly if they do not. The Kamasutra’s hero would also be termed ‘effeminate’ for the attention he pays to the lustrous locks on his head. Today, long hair in India has become the provenance of femininity, while masculinity is tied to short hair. Long hair for men is considered a rebellious style restricted to the entertainment industry, whose members also sport gleamingly waxed chests. For the rest of the Indian masculine world, it is acceptable for heterosexual men to have a hairy body and a bald head.

In stark contrast to these men, Indian women are expected to have plentiful hair on the head… Since long hair is now the sign of female respectability in India, women getting married want to feel like ‘real’ women. Glossy hair is the face (as it were) of female desirability in India.

These cascading locks on a woman’s head are expected to be in inverse relation to the amount of hair on her body. In following these strictures, women today have taken on the mantle of the Kamasutra’s male protagonist. Historically, though, the burden was shared more equitably.

…

Mir Taqi Mir extends this love of hair on the head to a disquisition about hair on the face. Usually, the growth of facial and bodily hair for both men and women marks the onset of puberty. This also marks boys and girls as young men and women, and therefore as people who are ready to have sex. Even those communities that practice child marriage in India will keep the child bride and bridegroom apart until they both start sprouting hair on their genitals and the rest of their bodies. However, when boys in Persian poetry start growing bodily and facial hair, they become less rather than more sexually attractive: young men with beards are considered lost to the register of attraction. This attitude invokes yet another historical disjunction: after all, facial and bodily hair on men today is taken as a sign of virility rather than unattractiveness.

But Mir makes his dismissive attitude to facial hair very clear across the course of his couplets. Addressing a ‘newly bearded one’, Mir proclaims: ‘Your face with down on it, is our Quran—/ What if we kiss it—it is a part of our faith.’ Here the facial hair being praised is nascent rather than developed, and so the boy may still be considered an attractively hairless boy rather than an unattractively hairy man. In a later couplet, once the down has grown into a beard, Mir expostulates that ‘His beard has appeared, but his indifference survives—/ My messenger still wanders, waiting for an answer.’ Mir is stunned that the boy’s arrogance has survived into manhood. He has a beard, so how can he continue to think of himself as being so attractive as to spurn prospective lovers, the poet asks. The onset of puberty is understood widely in Persian poetry as marking the turning point of attractiveness in young men. Mir wrote quite openly about the beauties of smooth skin—‘These pert smooth-faced boys of the city, / What cruelty they inflict on young men.’ Hairless youth is beautiful; hairy adulthood less so. Persian and Urdu poetry associates bodily and facial hairlessness with male attractiveness. In this, they join Vatsyayana who extols exactly this ideal of beauty for men in the Kamasutra.

Such an approach to beauty has led to the criticism that Persian and Urdu poetry is pederastic in nature. Praise of the hairless might well suggest that the object of attraction has to be young. But, as women around the world can testify all-too painfully, hairless faces and bodies can also be created at any age. In their fetishization of hairlessness, the refined male poets who love hairless boys are joined by heterosexual men who insist that their female objects of desire be depilated to within an inch of their lives. This explains the rich industry in hair-waxing and threading in India. As soon as they enter their teens, urban Indian women are encouraged to remove all traces of hair from their legs, arms and underarms, not to mention their chin (threading or waxing) and sideburns (usually by bleaching). Objects of desire are encouraged to be child-like by being hairless. In urban heterosexual relationships, this is true across the board—women are meant not to have hair on their bodies and faces if they are to be considered attractive. Unlike the parameters sketched by the Persian and Urdu poets, many homosexual subcultures globally revel in bodily and facial hair. But heterosexuality around the world seems fairly united in its insistence that women as objects of desire must have plenty of hair on their heads, and none at all on their faces and bodies. Women must look like pre-pubescent children. This is why they are so often referred to as ‘baby’. What passes as a term of endearment is really an insistence that women stay infantile in body and spirit.

…

Hair has been a marker of sexual attractiveness in India across gender. And across religions. If anything, hair has functioned in all the major religions of the world as the most potent symbol of desire. The adjectives we use to describe hair—luxurious, abundant, plentiful, cascading—all point to something sumptuous about hair that slips out of the band of restraint. Perhaps it is the fear of such abandon that makes religions clamp down on stray hair. On a recent visit accompanying my aunt to the Madurai Meenakshi temple, the security guard disapproved of the fact that my hair was not tied up. ‘No free hair,’ she shouted at me. I wanted to say that my hair was not free at all, that in fact I spend a lot of money on it. But of course what she objected to in my ‘free hair’ was sexual licentiousness rather than a possible economic bargain.

…

Perhaps the most famous tale about this complex knot of hair, desire and violence is to be found in the story of Draupadi from the Mahabharata. Even before the account of Draupadi’s hair comes up in the narrative, she is presented to us as a character with an interesting relation to desire. She is married to one of the Pandavas—Arjuna—but then, owing to a miscommunication, she is parcelled out among all five of the Pandava brothers as their joint wife. The Kamasutra tells us that any woman who is not a courtesan and who has had sex with five men is to be considered a loose woman with whom any man can have sexual intercourse. By this yardstick alone, Draupadi’s sex life is to be looked upon in the annals of Hindu mythology as ‘loose’. But despite these parameters, Draupadi is one of the few women in the history of desire in India who is not condemned for having multiple sexual partners. Indeed, having sex with five men is considered her dharma, and she is even allowed to have one child with each man.

Sometime after she is married to the five Pandava brothers, the Pandavas invite their cousins, the Kauravas, to admire their new palace in Indraprastha (later to become a part of Delhi). One of the chief attractions of this palace is the Hall of Illusions, in which nothing is as it seems. The Kauravas are depicted in this tale as the country bumpkins, at sea in the home of the urbane Pandavas. They cannot navigate their way around the Hall of Illusions—they assume a crystal floor is a pool of water, and a pool of water is a crystal floor, with the result that they fall into the pool, much to their consternation, and Draupadi’s amusement. Draupadi and Bhima laugh uproariously at the uncouth Kauravas, who understandably get upset at thus being the source of their host’s amusement. They leave in a rage. And when they come back, they return to take revenge. Duryodhana invites Yudhishthira, the eldest Pandava, to a game of dice, which the latter loses. Among the things he stakes on this game are his kingdom, his brothers, himself, and finally Draupadi. All the Pandavas and Draupadi now become slaves of the Kauravas, and Duryodhana’s brother Dushasana is sent to bring Draupadi into the court so she can be taunted with news of her new station in life.

Draupadi turns out to be a recalcitrant subject and refuses to come into the court. Dushasana then drags her in by the hair. Duryodhana gestures to his thigh as the seat on which Draupadi should perch, and Dushasana starts to disrobe her in an attempt to dishonour her fully. The legend goes that Draupadi prays to Krishna to protect her honour, and lo and behold, it seems like Dushasana can never get to the bottom of her attire—the saree simply keeps coming. Exhausted, he gives up, and Draupadi’s clothes stay on her body. This episode is commonly referred to as Draupadi’s ‘cheer-haran’ or ‘vastra-haran’, which means the episode in which Draupadi’s clothes are stripped off her. But it should more properly be termed the ‘Hairy Tale’ since what happens to Draupadi’s hair is of more import in deciding the course of the Mahabharata and the ruinous war in which the cousins get embroiled.

Draupadi gets dragged into the public court by her hair, which cascades as a sign of sexual availability. After narrowly escaping being disrobed, she vows never again to tie up her hair unless she is first able to bathe it in Dushasana’s blood. She prophesies that Bhima, one of her five husbands, will tear open Dushasana’s chest and she will bathe her hair in the gore. Until she is able to have that blood bath, however, she will not tie up her hair. Draupadi’s loose hair becomes the central concern in this entire episode. It is both the marker of her sexual humiliation, and the indicator of when that humiliation will end. Her hair becomes an actor in the theatre of the Great Indian War, the war of Kurukshetra that is central to the Mahabharata. Draupadi’s hair is a mighty weapon, and dance enactments of this episode, for instance, present it in all its gruesomeness. In a Kathakali version I once saw, Bhima rips apart Dushasana’s chest and, with his victim still twitching in the throes of agony, tears out his entrails from deep within the bowels. The entrails that emerge themselves look like long braids of hair, writhing in pain and dripping in blood. Draupadi is summoned, her hair washed in the blood so that there is little to distinguish her matted hair from the bloody entrails, and finally, her hair is tied up by a triumphant Bhima. This curtailed hair restores to Draupadi her chastity and modesty.

…Draupadi’s hair becomes a matter of life and death in the Mahabharata, as well as in its reimagination by artists after the fact. Hair is a major pawn in the battlefield of desire—people live and die according to whether a woman’s hair is tied up or left loose. Entire epics change course and acquire shape depending on what is going on with a woman’s hair.

This is the case again in The Story of Manu, when Varuthini is heartbroken after being rejected by Pravara. The force of her sexual ardour is made clear by the fact that her hair is not tied up, and is left to cascade down her entire body: ‘She rested her thick hair on her wrists, fragrant as lotus stems, and flowers were scattered everywhere as the hair came loose and, since it had grown so long, darkened her whole body as if the sky with its planets had fallen over her and made her still more beautiful.’ This thick hair makes desire beautiful, sexy, dangerous and sensual; it evokes the animal kingdom, the plant world, and the celestial stars. Her scattered hair leads to the plot developing in the way that it does, and Varuthini eventually has sex with the pseudo Pravara to produce a son who goes on to become the father of Manu, the hero of the epic. Hair is here all-encompassing and universal in its desirability.

So much so that even the stones cannot do without it. Erotic sculptures in India, from the 11th-century Khajuraho temples to the 16th-century bronze and ivory statues in the Nayaka kingdom of South India, display abundant hair as a part of their sexual package. Men as much as women pile up hair on their heads, and there is inevitably an equivalence of scale between the bun on the head and the breast of the woman. Male kings and courtiers have hair piled on top of their heads—hair here seems to be a mark as much of sexuality as of power. This intertwining of power and desire is familiar to us from centuries ago: when the male citydweller in the Kamasutra is taught the modes of acquiring power through sex, one of the first steps he has to take is to oil and comb and groom the hair on his head. The history of desire in India grows out of this long Indian obsession with hair and sexuality. Hair is the universal signifier of desire, power, exultation, loss and mourning. For both men and women.

…

So rich is this history of hairy desire in India, that it comes as no surprise to find out that India is the most desirable supplier of hair to the rest of the world. Indian hair is valued so highly on the international market that it makes up wigs and hair extensions at the best beauty salons globally. For his 2009 documentary Good Hair, American star Chris Rock travelled to India to get at the root of what makes good hair. Much of the hair for sale in high-end hair salons in the US comes from Indian temples that have turned into tonsure factories. Rock follows the journey of this hair from India to tens of thousands of happy customers abroad. Most suppliers specialize in a product called ‘Remy hair’, which is the generic name for a bunch of hair in which all the strands grow in the same direction. ‘Virgin Indian Remy Hair’ is considered the gold standard of Remy hair; it is the most highly priced product on the hair market internationally. The name itself—its virginal quality—suggests the impossibility of thinking of hair separate from desire. As though aware of this sumptuous cultural history, one of the top suppliers of Indian hair is called Desire Inc.