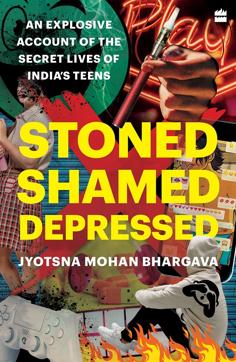

Excerpt: Stoned, Shamed, Depressed by Jyotsna Mohan Bhargava

“At any given time, hundreds of zombies – human ones, like Aarav – are staring wide-eyed at their screens without so much as a blink as they try and save the world by taking down the real ones – the creatures on their gaming consoles and computers. To them, the fictional characters in the games become more real than the humans they live with…” This extract from a book on the “secret lives of India’s teens” examines the widespread addiction to gaming

There was some funny business going on, thought the Class 5 students of a Delhi-NCR school. They found it odd that a classmate was absent on most days, yet his name was never struck off by the school. Even after they moved to Class 6, nothing changed. The missing boy, Aarav, still had his name on the attendance register. He showed up for a day before disappearing again. The students in the class stopped erasing his name from the absent list on the blackboard, they knew it was pointless because it would just have to be written again the next day. ‘He must be unwell,’ parents of his classmates speculated. The kids weren’t convinced. It turns out, both were not wrong.

The truth was that in Class 5, Aarav became involved in gaming. It was not some casual mobile game like simulated car racing or Candy Crush, although the latter some experts are warning may also not be as innocent as we think. The boy, who had a bigger build than most in his class, never really focused much on anything – at least his classmates thought he had no interest, little realizing that Aarav was in fact focused – only his calling was elsewhere.

Aarav was sucked into a gaming whirl so bad that no one quite knew who was playing who. As the dark hours ticked away, he stayed awake night after night staring at a screen and when the morning alarm rang for the rest of his classmates, his eyes finally found relief. Aarav couldn’t have made it to school even if he tried. For the school, though, it was a dilemma. Should they rusticate a student who had a fraction of the lowest mandatory attendance or keep the status quo with a child who needed the support if he was to be rescued? They did the right thing.

The tween had been ordering games online and one day even hacked into his father’s online shopping account. That was when his family realized that he was addicted. Aarav’s parents were given an ultimatum by the school to admit him to a de-addiction centre. For most of that year Aarav was in therapy, but that didn’t work out too well.

At any given time, hundreds of zombies – human ones, like Aarav – are staring wide-eyed at their screens without so much as a blink as they try and save the world by taking down the real ones – the creatures on their gaming consoles and computers. To them, the fictional characters in the games become more real than the humans they live with. One wonders though, who is trying to save the world here? If they become anything like Aarav, they will be the ones who will need saving.

In March 2019, two men barely in their twenties in Maharashtra couldn’t control their urge for a quick game and sat down to play on train tracks. A train duly came along and mowed them down.1 In April 2019, a sixteen-year-old hung himself from a fan in Hyderabad after being scolded for playing games when he should have been studying for his English test. In Mumbai, an eighteen-year-old reportedly killed himself after being refused a phone that cost Rs 37,000 to play PUBG, an online multiplayer battle game that ranks as one of the most popular games in India. In September 2019, a fourteen-year-old in Visakhapatnam4 committed suicide after his mother tried to end his gaming obsession. None of their parents could have imagined that what they classified as a tantrum or a minor affliction would change their lives forever.

‘At this age children are very experimental, there is a thrill of the internet anonymity which I think is a myth,’ says Nirali Bhatia. ‘It is the effect of the screen, it gets toxic and people don’t realize to what extent their other side comes out. The screen is changing our behaviour and thought processes because it’s a reactive place. It is governed by impulses and emotions. There’s no time to think.’

When video games first became popular, we were bloodthirsty for Atari – yet it was, by and large, non-addictive. Today when even Netflix addiction is a reality, gaming has its own take-off. Now it has become a compulsion for many, it is the reason for anger for some but either way, those who cannot go a day without playing are either harming themselves or destroying those who are closest to them. In September 2019, a young man of twenty-one in Karnataka beheaded his father after the parent objected to the son playing PUBG non-stop. It was the father who had gifted his son the smartphone he played on.

These episodes are all extreme cases, and might be few and far between, so parents may convince themselves that their kids are safe. But there are children like Mehul who met a stranger on a chat while gaming and then dropped everything to go meet him. The stranger lived in a town a few hours away, but that didn’t stop Mehul from getting into the car. The adults will also prefer to believe that majority of those addicted are older, but that too is not a safe assumption. Substituting a gaming console for family time by some has repercussions.

‘The most common age group for gaming addiction is fifteen to nineteen years which means that they got interested in gaming latest by the age of eleven,’ says Dr Manoj Sharma. ‘The children who are brought to us by their parents are predominantly from urban Bangalore, Chennai and Hyderabad. We see eight to ten cases per week. The number is only increasing with gadgets, leading to decreased communication within families.’ Dr Sharma works at the Service for Healthy Use of Technology (SHUT) Clinic in Bengaluru, widely recognized as the country’s first digital-detox clinic.

…Child psychiatrist Dr Sagar Mundada likened playing games to having a sweet treat, saying that gaming has the same effect on the pleasure centre of the brain as eating chocolate…

In random order: social media, drugs and gaming, especially for boys – have redefined the concept of a thrill, many of whom are now playing out their own version of Avengers. For those who think ‘it’s just a phase’ and will be as short-lived as the latest fad, the news may not be all good. There are chances, this may go the distance. ‘The gratification from social media and gaming is such that it is extremely difficult to resist,’ says author Nupur Dhingra Paiva. ‘So even if a child does not have other issues, they will end up creating some. In gaming, you can have a virtual world with comparatively little judgement and a sense of accomplishment that you don’t get in real life. Things in the real world take a lot of work, frustration and tolerance, and gaming takes the mind off other issues – homework, relationships, feelings, anxieties – making it a very attractive distraction. Also, a friend can abandon you. A game won’t.’

Instant gratification tempts the gamer, it is a world far away from the monotony of a classroom. In 2018, the WHO recognized that gaming was not all fun and games, that it had already manifested into something grave, and listed gaming addiction as a mental health disorder. The organization describes gaming addiction — to digital or video games — as ‘a pattern of gaming behaviour characterized by impaired control over gaming, increasing priority given to gaming over other activities to the extent that gaming takes precedence over other interests and daily activities.’ The numbers may be small for now but there is an upward trend. Unfortunately, in a country that still finds it hard to look mental health in the eye, many families may continue to miss the signs that their children are addicted to a game.

Simulated sex acts or violent sexual content can be found in games like Grand Theft Auto. The propensity to overstimulate can be judged simply by going on social media and witnessing the wave of hysteria before the launch of a new chapter of a popular game. ‘There is a void in the ecosystem,’ says psychiatrist Dr Samir Parikh. ‘We are left with very little to occupy the children. They need stimulation, including games, but those need to be both indoors and outdoors.’ …

Many homes now resemble the internet cafes of the ’90s, only the ones using the facilities are free boarders. The more the children play video games, the harder they resist any intervention or attempts to curb their obsession. Many don’t want to be an amateur anymore and play for the sake of playing. Like social media they seem to have found their calling – whether they are shooting from the shoulders of an animated character or keeping up with the peers, whatever gives their lives adrenaline and their hands the controls. And while they were out looking for dangers in the virtual world, they were caught out by the real world.