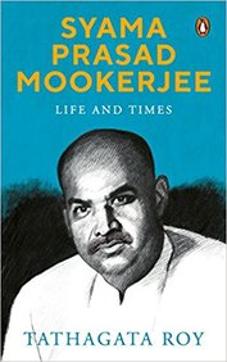

Excerpt: Syama Prasad Mookerjee; Life and Times by Tathagata Roy

Governor of Tripura, Tathagata Roy’s biography of Syama Prasad Mookerjee, founder of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, focuses on an important but forgotten politician. This excerpt examines his mysterious death

Dr Syama Prasad Mookerjee, unbeknown to himself, set out on his last and fateful journey from Delhi railway station at 6.30 a.m. on 8 May 1953 as the passenger train, carrying him and his entourage to Punjab on his way to Jammu, steamed out of the station. The compartment in which he sat had been bedecked with flowers and Jana Sangh flags. Guru Datt Vaid, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Tek Chand, Balraj Madhok and a few pressmen were there with him. Shortly before his departure, he issued a statement explaining his purpose of going to Jammu, namely to find out for himself the extent and depth of the Praja Parishad agitation and the repression let loose on the citizens of Jammu by Abdullah.

Explaining why he had not applied for an entry permit, the statement said:

Mr Nehru has repeatedly declared that the accession of the State of Jammu and Kashmir to India has been hundred per cent complete. Yet it is strange to find that one cannot enter the State without a previous permit from the Government of India. This permit is granted even to Communists who are playing their usual role in Jammu and Kashmir. But entry is barred to those who think or act in terms of Indian unity and nationhood.

Regarding his aim in going to Jammu, the statement said:

My object in going to Jammu is solely to acquaint myself with what exactly had happened there and the present state of affairs. I would also come into contact with available local leaders representing various interests, outside the Praja Parishad. It will be my endeavour to ascertain what the intention of the people of Jammu is, and to find out if at all there is any possibility of the movement being brought to a peaceful and honourable end, which will be fair and just not only to the people of the State but also to the whole of India.

He was thus, contrary to what Nehru and Abdullah had sought to project, not out to provoke the agitators and take them on the path of further confrontation with Abdullah’s government. Ever the constitutional politician, he wished to bring the agitation to an end whereby both the warring parties would be able to save their faces. Only, in entering the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir he had refused to take the permit to be issued by the Government of India.

The first stop on his itinerary was nearby Ambala, in Punjab (now Haryana). While on the train, however, Dr Mookerjee remembered that before leaving Delhi he had promised Professor Walter Johnson, a visiting American dignitary, that he would send him papers on the Jana Sangh; and also more importantly, that he ought to send some official intimation to Abdullah about his entering the state. In fact, he had fixed up a meeting with Johnson on 13 May, but possibly on the apprehension that he may be arrested, also told him that he may not be able to keep the appointment. In any case, he shot off a telegram to Abdullah which read, ‘I am proceeding to Jammu. My object in going there is to study situation myself and to explore the possibilities of creating conditions leading to peaceful settlement. I will like to see you also if possible.’ He sent a copy of the telegram to Nehru.

The train reached Ambala at about 2 p.m., and there was such a huge crowd on the platform that Dr Mookerjee had a hard time getting down. Even before he got down the president of Ambala Town Jana Sangh, advocate Raghbir Saran, showed him the latest issue of the Illustrated Weekly of India 4 which carried on its cover the pictures of Dr Mookerjee and Jayaprakash Narayan with the caption, ‘After Nehru, Who? Mookerjee or J.P.?’

From Ambala he drove down to Karnal via Shahabad and Nilokheri where he had to make unscheduled stops and make speeches. From Karnal he sent a short letter to his sister-in-law Tara Devi, describing the reception he had had so far. He also expressed his worry about his dear Hasu, his younger daughter, whom he had left back in Delhi. He had a special soft corner for this one, the quiet, withdrawn girl who had never known a mother’s love, and had moreover recently recovered from a bout of tuberculosis. He spent the night at Karnal and the next day drove to Panipat and addressed a huge meeting there; then he took a train to Phagwara, where he received a reply to the telegram he had sent Abdullah. It read, ‘Thanks for your telegram. I am afraid your proposed visit to the State at the present juncture is inopportune and will not serve any useful purpose.’ Nehru did not bother to send a reply, or even an acknowledgement.

After Phagwara, the next stop was Jullundur where he addressed a press conference. He also sent back Madhok from Jullundur and boarded a train for Amritsar. In the train an elderly person introduced himself as deputy commissioner of Gurdaspur (the district in which Pathankot is situated) and told him that the Punjab government had decided not to allow him to reach Pathankot. Upon hearing this Dr Mookerjee proceeded to make arrangements for his arrest, and decided, after consultations, that Guru Datt Vaid, the well-known Ayurvedic physician and author who was then president of Delhi state Jana Sangh, and Tek Chand, a young energetic worker from Dehra Dun, would accompany him and court arrest with him. But strangely, he was not arrested, neither at Amritsar nor at Pathankot nor anywhere on the way. A huge crowd of over 20,000 received him at the Amritsar railway station where he halted for the night. He met the local workers and talked to them. He was emphatic that he would go to Jammu whether Abdullah liked it or not. The journey from Amritsar to Pathankot was yet another triumphant march. Thousands of people greeted him at every station. He arrived to an unbelievable reception at Pathankot. A sea of people with folded hands stood on both sides of the bazaar through which his jeep passed. Just before his departure a ninety-year-old lady blessed him in Punjabi with the following words: ‘Oye Puttar! Jit ke avin, aiwan na avin (My Son! Do not return until you are victorious).’

Soon after his arrival at Pathankot, the deputy commissioner of Gurdaspur, who seemed to have preceded him, sought an interview with him. He informed Dr Mookerjee that he had been instructed by his government to allow him and his companions to proceed and enter Jammu and Kashmir state without a permit.

He himself appeared quite surprised that the orders that he was due to receive had been reversed. Little did he, or anyone else present there, know that the diabolical scheme that had been hatched had it that Dr Mookerjee would be arrested in Jammu and Kashmir state and not in Punjab, so that he would remain outside the jurisdiction of the Indian Supreme Court.

The next stop was the border check post at Madhopur on the River Ravi, one of the five great rivers of the Punjab, marking the boundary between the states of Punjab and Jammu and Kashmir. There was a bridge across the river, and the boundary lay at the midpoint of the bridge. Dr Mookerjee and his companions reached the check post at 4 p.m. The deputy commissioner of Gurdaspur and other officers present there saw them off at the bridge. But as soon as the jeep reached the centre of the bridge, they found the road blocked by a posse of the Jammu and Kashmir state police. The jeep stopped and a police officer, who said he was the superintendent of police, Kathua, handed over to him an order of the chief secretary of the state, dated 10 May 1953, banning his entry into the state.

‘But I intend to go to Jammu,’ Dr Mookerjee declared.

Thereupon the police officer took out an order of arrest under the Public Safety Act of the state signed by Prithvinandan Singh, inspector-general of police, dated 10 May, which stated that Dr Mookerjee ‘has acted, is acting or is about to act in a manner prejudicial to public safety and peace’, and that ‘in order to prevent him from so acting . . . Captain A. Azeez, Superintendent of Police, Kathua’ was being directed to arrest Dr Mookerjee and remove him under custody to the Central Jail at Srinagar. ‘All right,’ said Dr Mookerjee on reading the order and got down from the jeep. Guru Datt Vaid, Tek Chand and others also got down.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee, his private secretary, had been with him up to this point. In his last message as a free person Dr Mookerjee told Vajpayee and others to tell the country that he had at last entered the state of Jammu and Kashmir, though as a prisoner, and to carry on his work in his absence.

The police jeep halted for a short while at Lakhanpur. The threesome was put in another closed jeep which rushed towards Srinagar through Tawi bridge and Jammu city. The people of Jammu had assembled in thousands near Tawi bridge to receive their hero. They waited for him till night but did not notice a closed jeep passing the bridge at dusk. They reached Udhampur at about 10 p.m. and Batote at about 2 a.m., slept the night there, and reached Srinagar Central Jail at about 3 p.m.

From there he and his two companions were escorted by the superintendent of the jail, Pandit Siri Kanth Sapru, to a small cottage near the Dal Lake where he, one of the most prominent members of the Indian Parliament, the president of one of India’s national parties, was to spend the last forty days of his life as a prisoner of Sheikh Abdullah, ostensibly just for having committed the offence of acting ‘in a manner prejudicial to public safety and peace’.

It is important to note here that many are under the impression that Dr Mookerjee was imprisoned for entering Jammu and Kashmir state without a permit. This is a canard deliberately spread by Sheikh Abdullah himself, as he had done in a broadcast, for reasons best known to him. Dr Mookerjee mentioned this in a handwritten note to his counsel U.M. Trivedi for the drafting of his habeas corpus petition. In fact, on 11 May the state government of Jammu and Kashmir issued an ordinance through the Sadr-i-Riyasat that it is an offence to enter the state without a state permit, but as the order of Prithvinandan Singh, inspector-general of police reveals, Dr Mookerjee was not (and could not have been) arrested under that ordinance. On the day of the arrest, the only permit that could have been issued was one by the Government of India and not by the government of Jammu and Kashmir. But as we have already seen, the deputy commissioner of Gurdaspur told him that the Government of India had already decided to allow Dr Mookerjee to enter Jammu and Kashmir state without a permit. This reveals a very strange and suspicious chain of circumstances that have been discussed later in this chapter.

…

The news of the arrest created a stir all over the country. Protests, meetings and hartals took place in Delhi and other places. This gave a new impetus and direction to the satyagraha. Satyagrahis began to proceed to Jammu without a permit and court arrest. But neither Abdullah nor Nehru was moved. Abdullah (whether with or without the consent or knowledge of Nehru, we shall never know) had a scheme up his sleeve which he was determined to follow up.

The place in which Dr Mookerjee was incarcerated was really a small cottage which was converted into a sub-jail almost in the middle of nowhere, near Nishat Bagh, far away from Srinagar city. It was situated on the slope of the mountain range flanking the Dal Lake. It could be reached only by mounting a steep flight of stairs which must have been a hard task for Dr Mookerjee with his bad leg, and proved to be much harder later. It had one main room about 10 feet by 11, in which Dr Mookerjee was lodged and two small side rooms which accommodated his co-detenues Guru Datt Vaid and Tek Chand. There was no room in this ‘sub-jail’ for a fourth bedstead. When Pandit Premnath Dogra was brought there on 19 June a tent had to be pitched in the compound outside to accommodate him. The whole compound was covered with fruit trees and vegetable beds leaving only small lawn, smaller than a tennis court, for the detenues to move about. It was at a distance of about 8 miles from the city. There was also no arrangement for adequate medical aid.

…

What a way to treat one of the most important, possibly the most important, member of the Opposition in the Indian Parliament!

Madhok states that many letters to and from him were completely suppressed. It was later discovered that Abdullah had ordered that Dr Mookerjee be given no additional facilities without his express orders. None of his friends or relatives was allowed to meet him while he was in jail. His eldest son, Anutosh, applied for a permit to visit Srinagar to see him. By that time there was a change in the rules of issue of the permit, and it had to be done by the government of Jammu and Kashmir. It was refused. Some of his relatives were in Srinagar at that time.

They too sought an interview with him but were also refused.

The only persons from outside who were taken to him for the purpose of interview were Sardar Hukam Singh, whose visit was purely political and U.M. Trivedi, barrister, who met him as his counsel. Madhok also reports that a half-mad sadhu was inflicted upon him whose nonsense he was forced to hear. It was probably done to tell the world after his death that interviews were allowed to him.

It was his long-cherished desire to write a biography of his father, and he began work on it. He also used to write his diary regularly. He took it with him to the hospital as well when he was removed there on 22 June. It would have been the most authentic source of information about his life and work, thoughts and ideals and above all his own feelings, and about the events that culminated in his tragic death. But it was kept back by the Kashmir government after his death and has still not been returned in spite of repeated requests.

On 24 May, Nehru and Dr Katju visited Srinagar for ‘rest’. They never thought to visit their august prisoner and see how he was being treated there. Later, after his death, Nehru said he had inquired about him and was told that he was in great comfort, in a ‘picturesque villa’ on the Dal Lake. ‘Being told’ was enough for Nehru.

The pain in his leg, thought to be due to varicose veins, got more severe by 3 June. In a letter dated 6 June addressed to Tara Devi, he wrote:

I was on the whole keeping well, but the pain in the right leg has again worsened during the last two days. Moreover for some days I have been running [a] temperature in the evening.

There is a burning sensation in the eyes and face. I am taking medicine. I get to eat only boiled vegetables. Fish [almost a staple food for Bengalis] is not available. The doctor has instructed me not to stand on my legs in order to give them some rest. As a result I get absolutely no exercise, and therefore lost all appetite. I wake up very early and around 5.30 a.m. I get up, go to the garden and recite the Chandi stotra . . . the whole day hangs heavy on me . . . all that I get to do is to read, recite the Bhagavad Gita, some writing.

He was feeling despondent and depressed because of the confinement and having nothing to do –– it can well be imagined what a punishment it must be for such an active person to be doing nothing from morning till night.

On the receipt of this letter in Calcutta on or about 12 June, Dr Mookerjee’s brother Justice Rama Prasad saw Dr B.C. Roy, apprised him of his health and requested him to contact Kashmir.

Dr Mookerjee always had a problem with the pain in his leg but it had never earlier been accompanied by fever. Because of loss of appetite he was getting weaker every day. Barrister U.M. Trivedi had gone to Srinagar on 12 June to argue his habeas corpus before the Jammu and Kashmir High Court. The government insisted that he would have to take instructions from him in the presence of the district magistrate. The Indian Evidence Act lays down that communication between a client and his lawyer is totally privileged and no one can be compelled to disclose it, even in court. Trivedi refused to take instructions in the presence of the district magistrate, and had to move the high court again to permit him to take instructions in private. After the high court struck down the government’s orders, Trivedi interviewed him for three hours on 18 June. He found Dr Mookerjee, who had braved so many adversities in his life, weak and cheerless.

Pandit Premnath Dogra who was taken from Jammu to Srinagar on 19 June to meet him was also struck by his poor state of health and low appetite...

The same night he developed a pain in his chest and back and a high temperature. On the morning of 20 June the authorities were informed about it. Thereupon, doctors Ali Mohammed and Amar Nath Raina reached the sub-jail at 11.30 a.m. The former diagnosed the trouble as dry pleurisy and prescribed streptomycin injections. Dr Mookerjee protested that his family physician had advised him not to take streptomycin as it did not suit his system.

But Dr Mohammed said that that was a long time back; lately a lot of new facts had come to light regarding this drug, and he need not worry. At about 3.30 p.m. the medicine was received and the jail doctor administered one full gram of the medicine into Dr Mookerjee. In addition he was also administered some powder, possibly some painkiller (no prescription was made available to anyone), which, Dr Mohammed said, was to be taken twice a day, but could be taken up to six times if the pain persisted or became severe. According to Guru Datt Vaid, Dr Mookerjee requested the superintendent of the jail on that day to send thenews of his illness to his relatives. But no such intimation was sent nor any bulletin issued by the government till after his death.

The next day, on 21 June, excepting the jail doctor who was only an assistant surgeon, no other doctor, not even Dr Mohammed, visited him. The jail doctor administered another one gram of streptomycin. His temperature rose and the pain increased during the day.

…

At about 4.45 a.m. on 22 June an attendant woke up Vaid and told him that Dr Mookerjee wanted to see him immediately.

Vaid rushed to his room and found that his temperature had gone down to 97° F and he had perspired profusely. He felt his pulse and found it very feeble. He administered him some hot cardamom tea and clove water which gave him some relief. Dr Mookerjee told him that he had slept fairly well till about 4 a.m., when he woke up and felt a severe pain in his chest and had broken into a sweat. He was also feeling so giddy that he thought he would lose consciousness. He thought he should not disturb anyone at that ungodly hour, but was progressively feeling so weak that he was forced to wake up Vaid. Apparently he had had a severe heart attack, a myocardial infarction as it is medically known––possibly the second or third one after the ones he had in 1945 at Barrackpore (see Chapter 7).

At 5.15 a.m. the jail superintendent was informed about his deteriorating health and was requested to come with a doctor immediately. Dr Ali Mohammed reached there at 7.30 a.m. He suggested to the superintendent that Dr Mookerjee should be immediately removed to the nursing home….’

Meanwhile Trivedi came to see him at about 10 a.m. At that time Dr Mookerjee was propped up in bed, and Trivedi found him in a good mood. They had discussions about his case for about an hour.

At about 11.30 a.m. the jail superintendent reached there with a taxi (not an ambulance), and they walked down the steep steps from his room to the taxi. Dr Mookerjee was removed, not to any nursing home but to the gynaecological ward in the state hospital about 10 miles away. He was kept in a room on the first floor (probably he was made to walk up the stairs). One Dr Jagannath Zutshi, a house surgeon, was detailed to look after him, though not exclusively.

What took place in the hospital is still shrouded in mystery. Barrister Trivedi came to see him at 5.30 p.m. after completing his arguments in the court. Justice Killam was hearing the matter. Trivedi was confident that Dr Mookerjee would be set at liberty the next day when the judgment was to be delivered.

Trivedi said later that he did not find him the way he found him in the morning, but Dr Mookerjee said he was feeling better than in the morning. … Trivedi stayed with him till about 7.15 p.m. and asked the attending doctor what his true medical state was. The doctor reassured him by saying that there was no immediate cause for concern. As he was about to leave, Dr Mookerjee asked him to get him some reading material of his choice. Trivedi shook hands with him trying to feel his temperature, which he found to be normal.

There was a nurse on duty in the room and some policemen on duty outside. Trivedi asked for permission to visit him at 9 a.m. on 23 June, but the doctor told him that his X-ray was scheduled at 9 a.m., so he should come and see him at 8 a.m.

That was the last time Trivedi saw Dr Mookerjee alive.

When he left at about 7.30 p.m., Dr Mookerjee was weak but cheerful. Doctors in attendance told Trivedi that the worst had passed and that he would be X-rayed next morning and would be all right in two or three days.

But on 23 June at about 3.45 a.m. Trivedi was told by the police superintendent that Dr Mookerjee was in a bad state and the district magistrate had asked him to be at his bedside immediately.

He was picked up from his hotel to go to the hospital. Pandit Premnath Dogra and the two co-detenues of Dr Mookerjee in the sub-jail, Guru Datt and Tek Chand, were also asked about the same time to get ready to go to the hospital. They reached there about 4 a.m. and were informed that Dr Mookerjee had breathed his last at 3.40 a.m.

This is what Madhok wrote about his last days in his lifesketch titled The Portrait of a Martyr and Guru Datt Vaid and barrister U.M. Trivedi said in statements made on 25 June.

Apparently, when Dr Mookerjee had made known his intention to visit Jammu, Sucheta Kripalani paid him a visit. Sucheta, it would be remembered, was Bengali, and had married Acharya J.B. Kripalani, and had assisted Gandhi during his visit to pogrom-affected Noakhali in 1946 (see Chapter 8). This is what Madhok said (on tape):

Sucheta Kripalani had told him, so many others had told him, that you won’t go, Nehru will not allow you to return safe from there. Dr Mookerjee told Sucheta, ‘I have no personal enmity against Nehru, I am working for a cause, why should he have any vendetta for me?’ Then Sucheta told Dr Mookerjee, ‘You don’t know Nehru, I know Nehru, he looks upon you as his main rival and he will try to remove you from the field if he can and he is capable of anything.’

Madhok was not explicit as to whether he had heard this conversation with his own ears. Quite possibly Sucheta spoke in Bengali, which Madhok does not follow.

And then again, on tape:

So, when Trivedi was staying in Nedou’s Hotel, one day a Pandit came to him. He said, ‘I am a Jyotishi [astrologer], Dr Mookerjee is not going to return safe, please get him released as early as possible’ . . . In the same evening, a police officer came, he said, ‘I am so and so, but please don’t disclose my identity, Sheikh Abdullah has a plan, Dr Mookerjee may not be allowed . . . [inaudible]. His habeas corpus is being discussed today. Please see that you get the judgment tonight itself.’ He insisted that [the] judgment is going to be given today, and you see, that he is probably going to be released, that is, judgment is given today itself and he is released.

This biographer had also interviewed Sabita Banerjee, Dr Mookerjee’s eldest daughter, at her flat in Koregaon Park, Pune, on 24 April 2010, and she had a somewhat different tale to tell. She was a widow at that time, about eighty-four, but perfectly fit, absolutely lucid and used to live all by herself with only a help. Her daughter Manju lived in another flat in the same block of buildings. Her interview was transcribed and got checked by her. She died about a year later. This is what she had to tell about the last days of her father.

After Dr Mookerjee’s death his eldest son Anutosh asked for a permit to visit Kashmir. In the application one has to always mention one’s father’s name, and presumably for that reason his request for a permit was refused. Then Sabita and her husband, Nishith, decided to visit Kashmir in his place, but quietly, posing as tourists, with their two children. They did not apprehend any trouble [and they did not have any] because then, in married women’s applications, the husband’s name and not the father’s name was mentioned.

They had a nerve-racking experience there. They had decided, for fear of trouble and possible arrest, that they would not reveal their identity. They took up residence in a big houseboat on the Jhelum. A friend of Dr Mookerjee from his days in London, one Jatindra Nath Majumdar, happened to be visiting Kashmir at the time, also as a tourist. He came to visit the Banerjees in their houseboat, and they were chatting in Bengali when a bearer of the houseboat came to serve tea.

Majumdar mentioned Dr Mookerjee in front of the bearer and asked her if she had seen the house where he had lived. Sabita winked at him so as to suggest that he should shut up, but she was still secure in the belief that the bearer would not understand anything as he did not know Bengali. As soon as Majumdar left the bearer asked them if they knew Dr Mookerjee. She said they didn’t and that they were talking about him only because he was Bengali. The bearer said that he could show them the house where Dr Mookerjee spent his last days. And he did.

They took a taxi to a hillock by the side of the Dal Lake, and climbed up the stairs to the sub-jail at the top of the hillock, she all the while feeling how her dear Bapi [father] must have felt with his bad leg when he was forced to climb those steps. It was a small isolated bungalow at the top of the hill, windswept and forlorn. In the sub-jail they found three cots in one room, side by side. Sabita asked the bearer about the whereabouts of the doctor who treated him in his last days. The bearer refused to divulge anything, but said that he could take them to a person who had been there when he died. Possibly Miss Rajdulari Tikkoo, his regular nurse at the gynaecological ward at the state hospital. Dr Mookerjee always insisted on a Hindu nurse.

They went to her house in Srinagar. Two women were living there, the nurse and her mother. As soon as Sabita revealed her identity the nurse said she would not say anything and asked them to leave. By now the Banerjees were extremely emotionally charged. Sabita burst into tears, and begged the nurse to tell her, saying that she would never reveal her name.

Then the nurse gave it all out.

Dr Mookerjee had fallen ill and was taken to the ‘maternity home’ as she described it. There, on his last day, she was on duty. He was sleeping. The doctor left, leaving instructions that whenever he woke up he was to be administered an injection, for which he left an ampoule with the nurse. After some time he did wake up, and [she said to Sabita, ‘I don’t know why I did it’] she pushed that injection. As soon as she did it, Dr Mookerjee started tossing about, shouting at the top of his voice, ‘Jal jata hai, humko jal raha hai (I’m burning up, I’m burning).’ ‘I rushed to the telephone to tell the doctor and ask for instructions.’ He said, ‘Theek hai, sab theek ho jaiga (It is all right, he will be all right).’ Meanwhile Dr Mookerjee had fallen into a stupor. And that was the end of him.

Then she said, ‘I have committed a great sin, and I had to tell it to you. But I will leave this house immediately, because you will get back to Calcutta, and talk about this, and all what I told you is bound to get out. Then I’ll be murdered.’ In fact that is what she did. The next day when Sabita and Nishith went to look her up both the mother and the daughter were gone. The nurse had refused to give her name.

According to a report printed in the Organiser on 20 July 1953 and translated and reproduced in Uma Prasad’s book, Rajdulari Tikkoo, the nurse, tried to get hold of a doctor when Dr Mookerjee’s condition became critical but no doctor was available. Tikkoo then asked an orderly called Noor Ahmed to fetch Dr Zutshi. Dr Zutshi came immediately, and telephoned Dr Ali Mohammed for instructions. Meanwhile Dr Mookerjee’s condition deteriorated further and he died at about 2.15 a.m., not 3.40 a.m. Dr Mohammed arrived about half an hour after his death. The source of this report is not mentioned.

The communiqué issued after his death by the Kashmir government on 23 June, gave the report of doctors Ali Mohammed and Ram Nath Parhar, who were said to have been attending upon him…

The aircraft, with its sad cargo… reached Dum Dum airport in Calcutta around 8.55 p.m. amid cries of his relatives, friends and admirers.... A sea of humanity besieged the body, and the truck carrying it could reach 77 Asutosh Mookerjee Road only as late as 4 a.m., seven hours later, a distance normally covered in less than an hour….The fifty-second birthday of the departed leader was just two weeks away, on 6 July.

That night many people slept on the road in front of 77 Asutosh Mookerjee Road, waiting for the body to arrive. The next day saw a deluge of humanity accompanying the body from the house to the Keoratala cremation ground, near Kalighat…

Dr Mookerjee’s eldest son, Anutosh, followed by others of the family, did the mukhagni, the ritual touching of the flame to his mouth. And then the pyre was lit and the body finally consigned to flames. And thus ended prematurely, even before he was fifty-two, the journey of the great man who could have saved the country from many of the ills that overtook it in the subsequent years.