Excerpt: True to Their Salt by Ravindra Rathee

Indian soldiers played an important role in the expansion and downfall of the British Empire. This excerpt, which includes an extract from the introduction and one from a chapter on Indian soldiers in WW1, reveals the magnitude of their contribution to Allied victories in the World Wars of the 20th century and to India’s own struggle for freedom

Colonization and its reversal are strategic phenomena. Eventually, colonization is about the domination of a population by an external or foreign power. It is achieved by force, and ends when the dominating force is not sufficient and the resistance is more powerful. The British Empire in India was no different. It was based on the foundations of military force, which predominantly comprised of Indians.

One cannot fully understand the British Empire without delving deeper into the instrument that enabled the Empire in the first place — the Indian Army and the sepoys that marched in its ranks. Colonization of India, and its rushed independence in 1947 are best understood by focusing on the Indian soldiers who were at the core of British (Company and later Crown) rule in India.

The Indian Army was also the global “strategic reserve” for the Empire, and in many ways explains the “exceptionalism” of Britain in world history. When reviewed in light of the small recruitment pool within the British Isles and the limited financial resources that, by necessity, had to be focused on the Navy, the critical role that the Indian Army played in Britain’s predominant military position for almost a century and a half until the Second World War becomes clearer. This global military capability was achieved at very little additional cost to the British exchequer, as the Indian Army was paid for by Indian taxes, and Indian soldiers were grossly underpaid.

Indian soldiers made a pivotal contribution to the British Empire, and Great Britain’s unlikely development into a dominant military and industrial power. This book aims to bridge the knowledge gap that exists about Indian soldiers’ contribution to Britain’s history and rise, by examining key themes in the history of the sepoy in British service, and looking beyond the well-trodden snapshot of the two world wars.

This book charts how the East India Company came to acquire this magnificent army in the first place, at a time when civil war in eighteenth-century India led to the breakdown of indigenous military command and control structures. By exploring the various mechanisms used by the Company and Crown to maintain control over Indian soldiers, we gain an insight into the role that insecurities of the Raj officials played on Indian and British history.

This book looks at the socio-cultural and emotional universe of the Indian soldiers who enlisted in the Company and Crown Armies in India, and the value system that drove them to serve with such dedication and loyalty. The service conditions, pay terms and discrimination suffered by Indian soldiers is reviewed in contrast to their contributions and motivations. A number of mutinies related to service terms are also reviewed, which were often resolved by temporary corrective measures. Nevertheless, the discrimination against Indian soldiers continued until the end of Raj.

This discrimination was not just limited to pay and service terms. The worst impact of discrimination became apparent during significant defeats that the British Indian Army suffered in campaigns outside India. It affected the life chances and recovery of the soldiers when the British imperial forces encountered a stronger adversary. The book reviews the Afghan disaster in 1839–42, the Mesopotamian campaign during the First World War and the Singapore defeat during the Second World War to review the tragic consequences for the Indian soldiers.

This book also examines the role of soldiers in maintaining the faith of their ancestors in India. The most severe of mutinies, including the rebellion of 1857, were a result of fears related to religious conversion. As a result, the British colonial rulers were forced to ban missionary activities in the Army and the wider Indian society to a point. The sepoys thus served as an effective control over the coercive powers of British rule in India, drawing a line in the sand over matters related to their faith that, though tested, were never breached.

Finally, as the ultimate proof of their critical importance to the maintenance of British rule, Indian soldiers also gained India’s freedom from colonial rule after the Second World War. The history of decolonization as taught in Britain and India today lays too much emphasis on British “voluntary withdrawal” or the nationalist popular movement in India. In fact, it was the growing doubt about Indian soldiers’ continued loyalty to the British Raj that led to Independence. It was an attempt to punish the “mutiny” of the Indian National Army (INA) soldiers — who fought against Britain during the Second World War — that undermined the loyalty of the Indian soldiers of the Raj.

The role of Indian soldiers in Indian independence has been underplayed (and in some ways forgotten), both within Indian and British national narratives. Imperial officers and British politicians did not want to admit that fear was the reason for their relinquishing of the “jewel” of the British Empire — this did not suit the narrative of brave white men on a daring mission to civilize the world. It also did not suit the politicians who formed the new government of independent India, who preferred a narrative that emphasized the role of non-violent political movement, and therefore their own role, in achieving India’s freedom.

Chapter Five: True to Their Salt

A sepoy’s life is for someAnd his death is for othersBut all his discomforts and trials are his alone

— Shah Wali Khan of the Ambala Cavalry Brigade

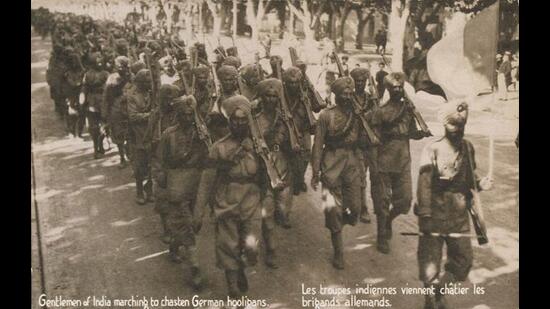

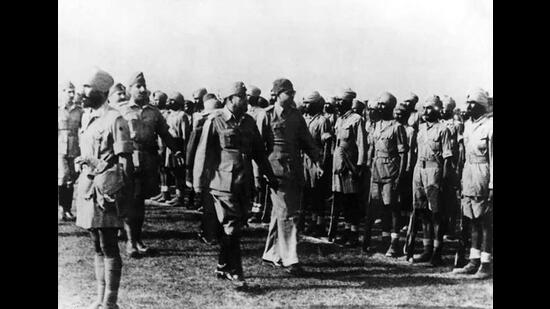

The British lines were holding on by the skin of their teeth in Flanders during the fateful month of October 1914. Numerically superior and better armed, the Germans were poised to smash through the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and open a route to the coast. Two divisions (Lahore and Meerut) comprising 28,500 Indian troops arrived to relieve the beleaguered BEF. Men born in the tropical climate of India suddenly faced European winters dressed in their khakis, meant for humid and hot Hindustan. Their rifles were of an unfamiliar pattern, and medical supplies and signalling equipment were short. The Germans had trench mortars, searchlights, hand grenades; the Indians had none of these, and were left to improvise grenades from jam tins.

Within days of their arrival, the underequipped troops were fed piecemeal into the front line. Almost one-third of them would never return home, sacrificing their lives in the fields of Flanders. While British soldiers fought for their homes and families, the Indian soldiers fought for something vague but deeply ingrained in their psyche — honour. They held no grudge against the German as an enemy on a personal level, except that he threatened the interests of the sepoy’s employer and the King-Emperor. This proved sufficient motivation for 8,000 of them to lay down their lives, “blown apart by shell fire, choked by gas or buried alive in soggy collapsing trenches”.

One man of these 8,000 was Dogra Jemadar Kapur Singh, the son of Jiwan from Ghagipur, Sialkot in Punjab in today’s Pakistan. Not much is known about him, except for his deeds in Flanders. Aged 26 at his death, he is likely to have been married, and possibly a father too, going by the pattern of Indian family life of the time. On the fateful day of 31 October 1914, Jemadar Kapur Singh was defending the position at Messines from a furious German assault as part of the Dogra Company of the 57th Wilde’s Rifles battalion. The German assault began at around 3 am. The Company of about 80 men was surrounded by nine German Grenadier battalions advancing at a “jog-trot” and making “raucous, guttural sounds”. The Dogra Company’s English commanding officer was badly wounded in the arm, and his men decided to evacuate him. Before leaving, he ordered the two surviving Indian officers to hold their position and under no circumstances to retire, unless the neighbouring units of British cavalry should do so first.

Taking their orders to heart, the two jemadars — Ram Singh and Kapur Singh —resolved to stand their ground. Unknown to them, the neighbouring British units were not as severely pressed by the German advance, and therefore did not withdraw. But the Dogras felt compelled to follow their orders to the letter. As night turned into morning, their position became increasingly desperate, and dangerous. All the men of the Dogra Company were killed one by one, leaving Kapur Singh as the last survivor. Eventually, by 8 am, the brave jemadar ran out of ammunition, except one bullet. Kapur Singh could not have been blamed if he now retired or decided to surrender. Standing in the trench without ammunition, and having lost all his comrades, he had fought as hard as any soldier could. His job was done; he had accounted for his “salt”. However, the young Dogra saw matters in a different light. As the Germans approached, Jemadar Kapur Singh, commander of the post and the sole survivor of the Dogra Company, took his rifle and put his final bullet into his own brain.

Merewether and Smith would later write:

Even this war can present few more devoted pictures than the death of these noble-hearted Dogras and the heroic Indian officer who chose rather to follow his men than to surrender.

Germans were known to have been kind to Indian soldiers taken prisoner, as they hoped to turn them against their masters. But Kapur Singh could not countenance a life as a surrendered prisoner, even if it meant death by his own hand. It is one thing to die in battle from enemy action, but it is quite another to value one’s honour more than life. This final act of offering one’s life, when there is nothing else left to give, is ingrained in the soldier’s code that men like Kapur Singh undertook, as part of an Indian martial tradition. In his final act, Jemadar Kapur Singh was following the millennia-old traditions of saka and jauhar. This was the essence of a soldier’s life, and there are numerous other examples to be found throughout the centuries of Indian history.

Continue reading with HT Premium Subscription