Review: The Quest Continues; Lost Heritage - The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan by Amardeep Singh

Besides tracking Sikhism’s cultural footprint in Pakistan, this book also underlines the fact that peaceful coexistence enriches lives

I’m not a Sikh or even a Punjabi. As a somewhat deracinated middle class Malayali Hindu raised in 1980s Bombay, no traumatic race memories shadowed my childhood. I first heard about the Partition from a Sindhi who had fled Karachi for the refugee camps of Ulhasnagar, and from the grandparents of Punjabi friends who made that fraught journey on trains across the border. The reminiscences were tinged with nostalgia for what had been left behind. And then there was that skein of horror. “We were scared every time the train stopped because, if the Muslims got on, they’d kill all of us,” our Hindi teacher recounted for the umpteenth time during a ‘free period’. There were many Muslim students at the Catholic school I attended. They looked on mutely. We were Indian school children together at a peculiar point in history when Amar, Akbar and Anthony were beginning once more to turn their jaundiced eyes on each other, just after Indira Gandhi and the Delhi massacres but before Babri Masjid and the Bombay bomb blasts. No, we didn’t start the fire but we’ve been caught in that hot-cold conflagration ever since.

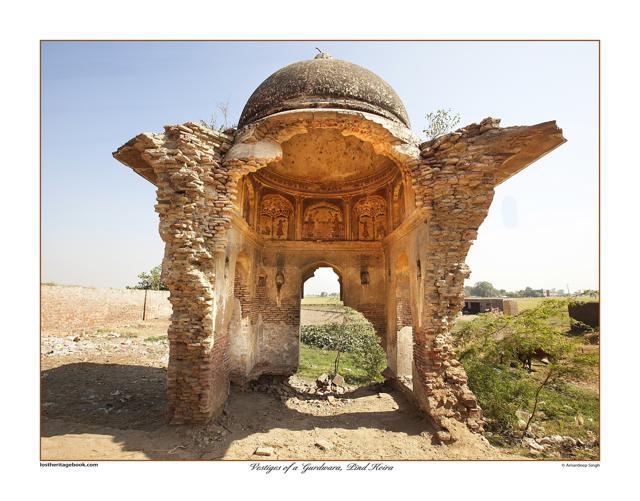

I thought of all this as I flipped through Amardeep Singh’s superb The Quest Continues; Lost Heritage – The Sikh Legacy in Pakistan. A follow up to his earlier volume on the same subject, Singh’s work clearly emerges from a place of intense religiosity and ethnic loyalty, from his need to explore the cultural roots of the Sikh community. While the first book was based on the author’s explorations across 36 cities and villages in Pakistan, the second takes in Pakistan Administered Kashmir, Sindh, Balochistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Pakistani Punjab.

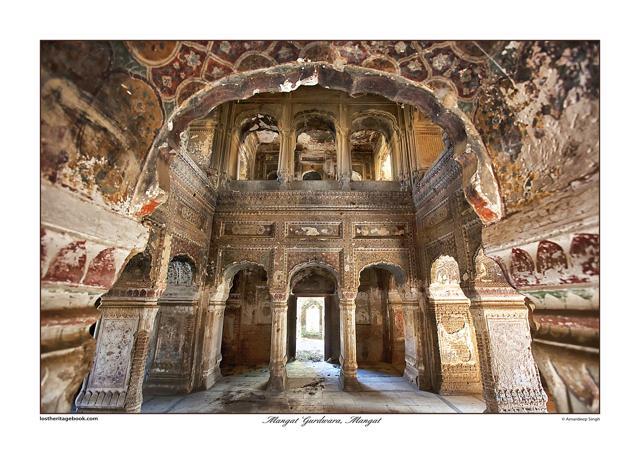

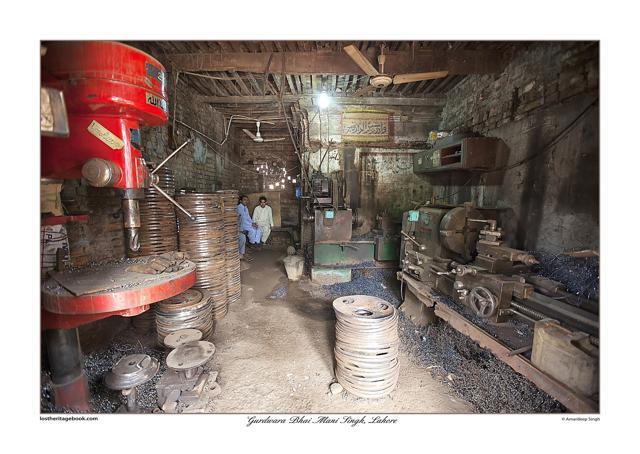

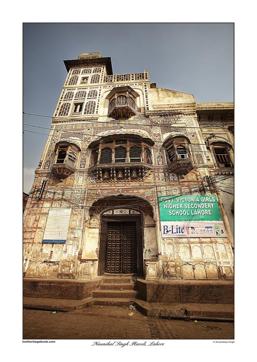

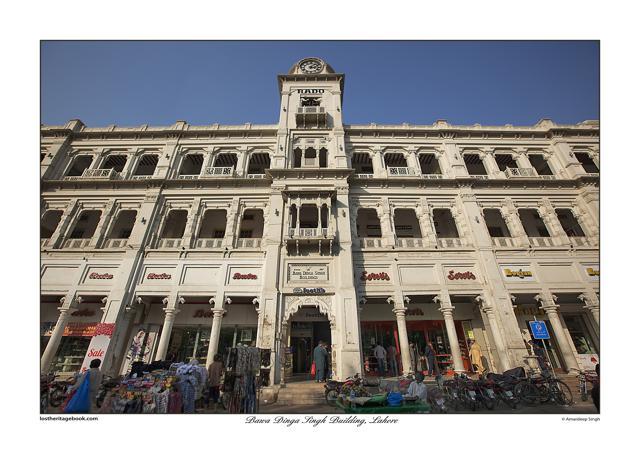

The supporting photographs are spectacular and the writing is personal, devoid of unnecessary stylistics and rich in anecdote. Most rewardingly, it places historic events and personalities in context. So a picture of the foundation stone of the Khalsa High School, Rawalpindi, laid by HH Sir Michael Francis O’Dwyer, Lieutenant Governor of the Punjab on the 1st of August, 1913, is accompanied by a paragraph reminding the reader that it was under O’Dwyer’s watch that Colonel Reginald Dyer led troops to Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar leading to the deaths of 379 unarmed civilians there. With Partition, the entire Sikh population of Rawalpindi left for India and the Khalsa school eventually became the Government Muslim Higher Secondary School.

The chapter on Faisalabad, formerly Lyallpur, offers up these nuggets: “The Sufi singers, Fateh Ali Khan, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Rahat Fateh Ali Khan grew up in the by-lanes of Faisalabad. Teji Bachchan, mother of the famous Bollywood actor Amitabh Bachchan, was born here to the Sikh family of Barrister Khajan Singh. She grew up learning and performing Kirtan at the gurudwara in Rail Market. Last but not least, it was here that Master Sunder Singh Lyallpuri founded the ‘Hindustan Times’, the English newspaper which was later sold to the Birla family in 1933 and has today grown to become India’s national daily.’

Then there’s the story of Mirpur in Kashmir, where many Hindus and Muslims sought refuge but were attacked by tribesmen from the North West Frontier. Of the 10,000 refugees apparently only 1,600 survived. “Ironically, Mirpur, the hill city that had 80 percent non-Muslims was wrenched of its secularity. After 1947, Mirpur became a 100 percent Muslim city. However, with the construction of Mangla Dam, Mirpur was submerged under the reservoir in 1967. This resulted in yet another wave of migration towards Britain. Today, around 70 percent of the British Pakistani community is from Mirpur. In a span of 20 years from partition, the old city of Mirpur had disappeared and its population dispersed.”

The power of a work can be judged by how effectively it spurs the reader to embark on intellectual journeys of her own. The story of Mirpur reminds me of camel catcher Paddy McHugh’s account of the million wild camels that now roam the Australian Outback. “They were all brought from what is now Pakistan to build the railways and then when motor vehicles became popular, they were freed”. The collapse of the Raj was responsible for the emergence of British Asians, the creation of refugee communities of different religious affiliations across the subcontinent, and, rather bizarrely, the colonization of the Australian bush by the Indian camel!

The author also touches on a range of subjects including how “cultures and languages have now been boxed into religious realms”, the equations between Pashtun Sikhs of the Swat valley and the Nanakpanthi Sikhs, and the syncretic nature of the Hindu-Sikhism practised in Sindh. This could have been an anodyne romp through important sites in Pakistan that carefully left out difficult issues. Amardeep Singh does not take the easy way out. But while he doesn’t avert his eyes from scenes of tragedy, like the well of Thoha Khalsa where women committed mass suicide, he urges the reader to view Partition with a degree of distance and imbued by the spirit of forgiveness. Here he is on Muhammad Aslam (88) who was 18 when he witnessed 25 Sikh women jump into the well to protect their honour: “With teary eyes, Muhammad Aslam looked into the well saying, “This is the site where the girls jumped and I helplessly stood in a corner. I still wonder why I did not make an effort to stop them. I was not a part of the mob but was afraid of the miscreants who had turned us against our own brothers and sisters. Years later, the event still haunts me.”

The Partition continues to cast its malign shadow on the Indian subcontinent and influence how its different communities and countries interact with each other. It affects personal and communal relationships as it does foreign policy.

Read more: Rolling rotis in Amritsar’s Golden Temple

This is an important book not just because it’s a listing of sites important to Sikhs and because it reminds readers of the tragedy of Partition but because it transcends that to make people of different faiths see that peaceful coexistence enriches lives, that bitterness must be overcome, and that we must learn from history instead of being condemned to endlessly repeat it.