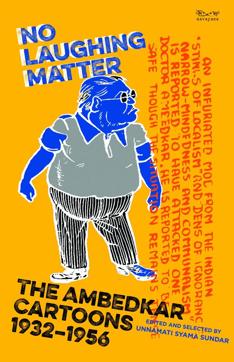

Review: No Laughing Matter: The Ambedkar Cartoons by Unnamati Syama Sundar

Unnamati Syama Sundar’s book, which shows how cartoonists between 1932 and 1956 presented Ambedkar unflatteringly, is a step towards understanding the caste impulses that drive visual cultures in India

When a controversy exploded over a cartoon depicting BR Ambedkar in May 2012, freedom of speech quickly became the fulcrum of the row. A large section of the commentators berated Dalit leaders for taking offence at the cartoon that showed Jawaharlal Nehru with a whip, egging on Ambedkar riding a snail, and said the eventual withdrawal of the cartoon was a defeat of free speech and innovative pedagogy. Some even lamented the “blind worship” of Ambedkar.

Out of the churn of this row was born Unnamati Syama Sundar’s No Laughing Matter: The Ambedkar Cartoons, in which the cartoonist-scholar unpacks 122 cartoons featuring Ambedkar published in major newspapers between 1932 and 1956.

Each scan of a cartoon, uncovered by Sundar digging through archives and poring over microfilm, is accompanied by an exposition of the social and political questions of the time through an annotation and a short, pithy, if somewhat acerbic commentary, given by the writer about the cartoon being depicted.

A casual read is enough to establish some glaring patterns: cartoonists cutting across publications often drew Ambedkar in humiliating postures, India’s first law minister is always the shortest in the picture, oftentimes a woman and sometime a sex worker. The few positive depictions see him as a thread-wearing Brahmin, a mutilation of his lifelong anti-caste thinking.

Laid out chronologically, the cartoons focus on three main aspects of Ambedkar’s work: His drafting of the Constitution, his work on piloting the Hindu Code Bill and his decision to leave Hinduism and turn to Buddhism towards the end of his life.

Owing to the reams written about Gandhi and Nehru in particular, and their depiction in newspapers, the uncharitable treatment is particularly galling. In Don’t Spare Me Shankar, for example, Nehru always comes across as a statesman and tall leader even though he is lampooned for his policies. In contrast, cartoonists show no hesitation in depicting Ambedkar as an amoral, avaricious leader with little moral imperative – even drawing him as a dog and a gorilla. Through his commentary, Sundar is able to highlight the caste supremacy that underlines this ‘creative licence’ and asks the reader what kind of systemic power structures can ensure commentators and cartoonists spend no time engaging with his work or ideas but caricature him.

Some of the harshest cartoons deal with Ambedkar’s decision to convert, his anger at the Congress party and his doomed political alliances -- he is repeatedly depicted as a petulant child, a man abandoning his constituents and responsibilities, and an opportunist who is at the mercy of the Congress and not a leader in his own right. In contrast to the zeal of the newspapers of the day devoting time and resource to Gandhi, Nehru and other tall Congress leaders, the bulk of the engagement with the lawyer-economist-academic Ambedkar is scorn.

With the benefit of hindsight, there are three takeaways. One, that Ambedkar was fairly alone in his work on drafting the Constitution and then with the Hindu Code bill – if one looks past the lampooning, it becomes clear that in cartoon after cartoon, he is depicted as the only person at work. Second, for all the jostling that his legacy has ignited in the past decade, there was little support for Ambedkar’s legislative and social agenda at the time from either the left or the right – the communists and the hardline rightwingers were united in their criticism of him. And third, that no social commentary is devoid of social impulses and the distinctly casteist, sexist representations of Ambedkar are also a reflection of academic and media cultures at the time.

Read more: BR Ambedkar: In his own words

The book is a significant step in understanding the caste impulses that drive visual cultures in India – a subject that is not widely written about, and even less from a perspective that sees caste as a leading influence. The detailed annotations and commentary about each cartoon make possible the reading of the book as a handy guide to the constituent assembly debates, the early days of Indian government and the republic’s first election.

But most importantly, the book delivers a crucial lesson on the 2012 controversy and freedom of speech, which it argues cannot be unalloyed. A debate is truly free when all sides have been given adequate space to articulate their view, not when one side has harnessed its historical head start to establish the right to set the discourse, and not expect backlash from communities and cultures it erases.