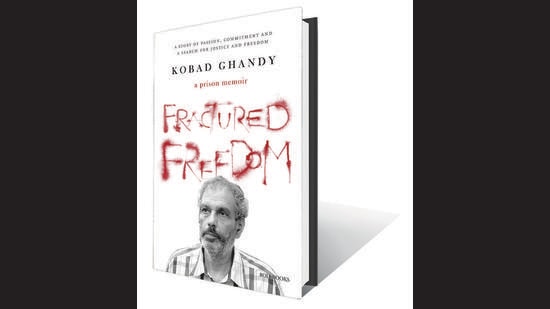

Review: Fractured Freedom - A Prison Memoir by Kobad Ghandy

A moral lesson for modern India, this is a book that shows us that jail need not be the end of activism or the struggle for truth and justice

The meeting of inmates with their lawyers in Jail Number 3 in Tihar in Delhi is conducted in the Deputy Superintendent’s room. The inmates sit on plastic stools; the lawyers sit on sofas and chairs. It was there that I first sighted Kobad Ghandy. My lawyer friend and I both noticed him at the same time. He had a stash of envelopes with him and patiently parried the sneers of an officer who chose that moment to show Kobad the fallacy of his views, thereby snatching away precious minutes from a prized legal mulaqat.

In those days, a visit to the surprisingly well-stocked library in Jail no 3 was the life-saving refuge I sought. Unbeknownst to me, Kobad and I were reading some of the same books from that library. A collection of stories by Anton Chekhov, for instance, including a marvellous portrait of the good doctor by Maxim Gorky. There were other books of common interest, including a volume of Justice Tarkunde’s writings, with marginal jottings by Kobad’s dear friend Afzal Guru; the same Justice Tarkunde who had played a key supporting role in the early days of Kobad’s activism in Bombay in the 1970s. There are several other serendipitous instances that dot this invaluable memoir which should be compulsory reading in our schools.

How and why did Kobad, or Koby, who swam at the Willingdon Club, played tennis and golf, studied at the Doon School with the likes of Sanjay Gandhi, Kamal Nath and Navin Patnaik, and at St Xaviers and London, end up working and living with the poorest of the poor is one of the most important questions for our times. I also went to Doon some 25 years after Kobad. Even then, it insisted on promoting all round excellence rather than narrow academic success but mostly produced students who flourished in the corporate world. So how did Kobad come to be what he became? It is a question that he answers in the first part of this sparse memoir. He was traversing the beaten path, following in his father’s footsteps as he journeyed to England to become a chartered accountant. But exposure to racism, to political currents in England, and a chance encounter with a biography of Norman Bethune, the Canadian doctor who lived and worked with Chinese Maoists, radicalized him. This led to years of self-study of Marxism and Maoism at the British Library and at the British Museum, not unlike Gandhi or Marx himself, and a stint in a British jail, after which he decided to throw away a promising career and returned to India. Surprisingly, his corporate Parsi father seemed understanding of this apostasy.

At the time when Kobad began his political journey in India, the world was full of radicals and the journey from Presidency College, Calcutta, to becoming a victim of a police bullet as a Naxalite was not uncommon. Those who could not become romantic revolutionaries stayed on to become romantic radicals in prestigious academia, or resurfaced as successful politicians and corporate NGO wallahs. But Kobad chose a different kind of praxis, one where working with the poorest meant living like them in the Dalit chawls around Worli in Bombay. At the height of the Dalit Panther movement, he endeavoured, in vain, to persuade his Communist comrades to accommodate caste in their revolutionary ideology. He pays homage to some of the stalwarts of this movement, to Namdeo Dhasal and Daya Pawar, and to other committed comrades such as Ravi, and Arul Fancis, who became his friends for life. It was also here that he met Anuradha, herself the daughter of committed Communists, and this memoir is both an ode and a heartbreaking love letter to his wife.

Even by the revolutionary standards of the 1970s, Kobad and Anuradha were unusual. Where Kobad was shy and introverted, Anuradha was outgoing, loving, simplicity itself, but equally ferocious of commitment. Anuradha could bring even diehard ideological opponents like Satyadev Dubey and Vijay Tendulkar on board for a good cause. They worked together in chawls and bastis, with domestic workers, with mill workers, and lived like them. They gave up not just their privileges, or comforts, but also their inheritance. Kobad was left a huge flat in posh Babul Nath. He sold it and used the proceeds for their organization. They met their parents sparingly, they chose not to have a child, they moved out of Bombay to Nagpur to work in the poorest of Dalit bastis there. They fought for the rights of all kinds of workers, not just for the rights from their employers, but also for rights from the state. This was not a struggle for some abstract revolution, but for making an everyday, concrete difference to the lives of some of the poorest and the most disadvantaged. The result was not mere upliftment, but also empowerment. Those who think that only tycoons who generate employment make a difference to society should study the contribution that back-breaking everyday struggle can make to ordinary lives. At Nagpur, they lived in Indora, the notoriously poor basti; they cycled and walked for hours in the infernal Vidharbha sun; Anuradha taught at the university, and also carried on her work with oppressed women, while Kobad organized rickshaw workers, or factory and biri workers in and around Nagpur. At the same time, they worked with radical cultural groups, with Lok Shahirs such as Vilas Ghoghre and Sambhaji. Among the people they trained was one Surendra Gadling, a lawyer, who is presently in jail for his supposed involvement in the Bhima Koregaon uprising, which forms another circle in Kobad’s life. They were imprisoned, they lost their family members, they suffered debilitating ailments but they carried on until Anuradha was thrown out of the university for her political work. They returned to Mumbai, but instead of recuperating Anuradha chose to travel to Bastar, where she worked with Adivasi women, battling sclerosis, and malaria until she succumbed to them. Many of their Mumbai friends were conscientious but few went the whole length as they did, and yet they dealt with their deprivation without censure, without righteousness. This is the very model of a life of commitment, of equality and of self-sacrifice. In talking of the both of them, one cannot help but quote Shakespeare:

“Only he acted from honesty and for the general good. His life was gentle, and the elements mixed so well in him that Nature might stand up and say to all the world, “This was a man.”

Instead of being lauded, of earning laurels and awards, of being held up as the paragons of what intellectuals should do in a poor society, instead of being admired and cited as exemplars of a noble life, what they got instead was Kobad’s arrest and vilification soon after Anuradha’s death. Was Kobad a Maoist? He doesn’t deny or admit that, but he certainly admired many things that Mao’s China achieved. It is also true, whether one agrees with their methods or not, that the Maoists are fighting for some of the poorest, most oppressed, most backward places and peoples of India. Kobad denies supporting violence or being a member of its politburo. He abhors violence, but would also like to alert us to the uncountable everyday acts of violence that the state and the powerful wreak on the poor. However, after 10 years of incarceration, umpteen cases, in seven different states of India, the state could prove nothing against him. The upholders of the ‘law and order state’ ought to respect the law as it worked in his case here.

The second part of Kobad’s memoir is an account of his jail life, horrid no doubt, but also full of surprising twists. His friendship with Afzal Guru, the Kashmiri accused of the Parliament attack is about love between two outcastes from two different extremes, who find common cause in poetry, in Rumi, and in intellectual discussions over a cup of tea in the most benighted corner of the country. Tihar, as Kobad saw it, was the most impersonal, the most horrid jail he experienced, aggravated by the uncouth and bullying character of the officials who guard it. The role of officialdom is to break your spirit, to lobotomize you, and the worst aspect of imprisonment is not privation or discomfort but the indignity and humiliation that you are subjected to at every turn. For a while, he was transferred from one jail to another every three months, and in each of these places, he would have to write applications for his medicines, for his mulaqat, for his books, his spectacles, his treatment. It is a tribute to his courage that he used every stratagem at his command, from writing applications and articles, to launching hunger strikes, to continue his fight for his rights there. In the course of that journey, he found unlikely respect and sympathy from dons such as Brajesh Singh, Sunil Rathi and Kishan Pahalwan who saw him as a rebel, who saw his fight as just, who saw him being wronged. In a classic fable of the wrong being good, it was only the outlaws who saw through the perfidy of the law. But in the course of that decade Kobad also found some very honest judges, who went out of their way to ensure justice to him, and also lawyers, who were willing to fight for him. Many of these lawyers themselves emerged from a revolutionary struggle in different parts of the country, which shows that even failed movements leave behind enough residue of commitment long after their passing, even if individuals soften their stridency. From Khalistanis and Punjabi gangsters who idolize him, to Maoist mafias in Jharkhand jail, to the young cops in Surat who listen eager-eyed to Kobad’s narration of revolutionary struggles, to a homage to comrades, judges and cops, Kobad’s life in jail is absorbing and no less revolutionary than the one outside. Throughout, he continued to read, to write, to reflect, even to publish, including a five-part essay in Mainstream on freedom through history. Many of his supporters and comrades in this journey such as Gautam Navlakha, Anand Teltumbde or Varvara Rao, themselves later met the same fate as he did. It is also heartening to learn that many of his friends and family, such as his sister Mahrukh, his theatre director brother-in-law Sunil Shanbag and his wife Rita, his school friend Gautam Vohra, remained steadfast allies and supporters.

Still the question remains, why should such a man have been in jail? He was a grassroots activist ameliorating the lot of the weakest section of society, there was no conspiracy or act of violence that he was shown to be involved in, and yet he spent nearly a decade in jail. This shows us a side of the state which remains constant, irrespective of regime change. His jail experience also shows us, especially relevant at this juncture, that jail need not be the end of one’s activism, or one’s struggle. That it is possible to struggle for truth and justice even within the deep caverns where by all forgot men rot and rot, and that not every official in prison, police or judiciary has abandoned a sense of fairness. Therefore, one must continue the good fight within the system in order to fight the system. It was, after all, judges such as PK Jain and Reetesh Singh, who not only helped provide him medical treatment but also eventually acquitted him. But to understand the importance of being Kobad one must counterpose the support he got, especially within radical civil society and the media, to the lot that befalls less noble victims. For instance, the poor Bombay blasts accused, whose heroic saga is no less inspiring than Kobad’s as seen in Abdul Wahid’s bone chilling account Begunah Qaidi.

The last part of Kobad’s memoir relates to his reflections on revolution, society and social change. Remarkably, he is satisfied with his life despite the wasted decade of imprisonment. The revolution may not have arrived, but the millions of hours, by thousands, working for the uplift of the poor have not been wasted, will not be wasted, as transformed individuals work to transform society. Consistently for five decades now Kobad has tried to alert his leftist comrades to the importance of caste dialectics to progressive politics in India. But in reflecting upon Marxist politics Kobad asks why it seems to be in retreat everywhere; what has happened to the efforts of millions of men and women to bring about a utopia on earth? He discovers that it is not enough to struggle for equality, or for economic emancipation. One must also strive for happiness in society. Happiness in society will not come about if we merely establish a dictatorship of the proletariat but its leadership turns out to be autocratic or tyrannical. He asks, “To what extent have we been able to use our conscious effort to counter the negative within ourselves and the environment. For, if we are unable to do this, no sustained social change is possible, as we see with what has happened to the leaderships in the erstwhile socialist countries.”

Like Gandhi earlier, Kobad would now like a politics where individual transformation is as important as social upheaval. What that needs is freedom, freedom from ego, from greed, from complexes, from vanity — all of which pervades leftists and rightists alike. As he says elsewhere,

“The more pertinent point is that though we may have an excellent grip on the laws that govern society, we may also be immersed neck-deep in all sorts of fears, jealousies, insecurities, pettiness, etc. With all this baggage can we still be said to be free? Far from it. We would be in a state of extreme unfreeness, entangled in a web of complexes and distorted behavioural traits.”

In following Marx, Kobad would like us to also think of Freud and the complexes that psychologically construct us as emotional beings, with all our foibles and weaknesses, which do not disappear merely because we follow the right opinion, or the right leader. Kobad’s ideal revolutionary is Anuradha, simple, joyous, free from complexes, loving, giving and free of the temptation to become a power holder, which does not cease to exist simply because a party is out of power. Indeed, one knows many a so-called progressive who uphold the right causes but are atrocious in their personal affairs. Ironically, and antithetically for Kobad, joy, simplicity, freedom, some of these are traits that his followers also associate with Gandhi. Kobad does not say it, but what he perhaps desires is a revolutionary like Anton Chekhov as Gorky described him —

‘It seems to me that in the presence of Anton Pavlovich, everyone felt an unconscious desire to be simple, more truthful, more himself… of a beautiful simplicity himself, he loved all that was simple, real, sincere and he had a way of his own of making others simple.’

What do they know of revolution who only revolution know? Without love, without generosity, without abnegation, without a revolution in the human beings who lead it there cannot be a true revolution. The importance of this memoir and of being Kobad lies in shedding privilege, in adopting poverty and struggle, in choosing the right life, in suffering wrongs for it, and yet remaining steadfast. Fractured Freedom is a moral lesson for modern India, which both the Left and the Right would do well to heed.

Mahmood Farooqui, a Rhodes Scholar, is an award winning performer and writer, best known for reviving Dastangoi, the lost Art of Urdu storytelling. His last book was A Requiem for Pakistan: The World of Intizar Husain (Yoda, 2017). He runs the Drama class in Jail no 3 in Tihar.