Slipping on inflation

The PM wants to curb inflation but not at the cost of growth. Also part of our economic narrative are the stories of those on the margins — inflation pushes them back into the poverty trap. Abhijit Patnaik and Kamayani Singh write. View from the farm

Last year, Meerabai, 30, and her husband Mantu Lal, 35, left their village in Rajasthan to get on a bus to Gurgaon. They hoped the millennium city's construction boom would help them escape poverty.

The arithmetic was quite simple. They would work on one of the myriad construction sites in the satellite town, earn around Rs 5,000 a month, spend Rs 3,000 and send the rest back home, where they left behind three of their five children.

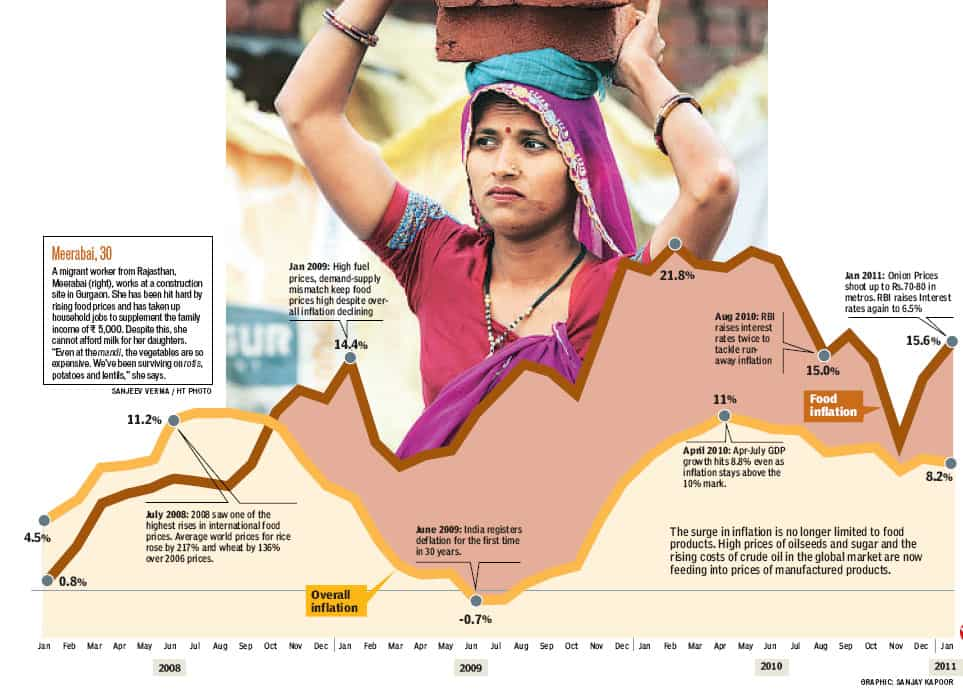

India's rapid economic growth in the past two decades may have helped pull millions like Meerabai out of poverty, but the spike in inflation - especially in food prices - over the past year threatens to undo those gains.

"I never imagined Gurgaon to be so expensive," says Meerabai, from the construction site of a private house in Gurgaon. "I don't have enough money to even buy milk for my 18-month-old daughter. She just eats dal (lentils) that I cook for all of us."

Reining in inflation has emerged as an overriding priority, as also a challenge, for the UPA government. The Reserve Bank of India has raised interest rates seven times in the past 12 months; foreign investors are getting wary and showing it - FII inflows turned negative in January; and the recovery from the global slump of 2008 that won India praises from across the world is slowly losing steam.

The surge in inflation is no longer limited to food products. High prices of oilseeds and sugar and the rising costs of crude oil in the global market are now feeding into prices of manufactured products, forcing policy makers for a trade-off between growth and inflation.

It's a double whammy for the poor. While high food inflation turns into a tax as they spend a majority of their income on food, new jobs are drying up with slowing growth.

As finance minister Pranab Mukherjee prepares for the annual budget, the likes of Meerabai are hoping against hope - can the government bail them out?

The reality is Mukherjee's options are limited, and chances are Meerabai's battle against poverty would prolong.

Government clueless

The government response to high inflation has ranged from knee-jerkish to one of helplessness. "I am not an astrologer. But I am confident that the price situation would be brought under control…" said Prime Minister Manmohan Singh on January 20. The food inflation rate that month soared to 15.6%. Singh's top aides in the government have made similar statements in the past, reinforcing how clueless the government remains about the price situation.

Take the case of skyrocketing onion prices last month that agonised consumers like Meerabai.

"On onion prices, we all got it wrong. No one had any idea this was going to happen," says Abhijit Sen, member, Planning Commission. "The problem is our complete inability to foresee what is going to happen. We need a greater ability to predict since unusual rain patterns are only going to become more frequent."

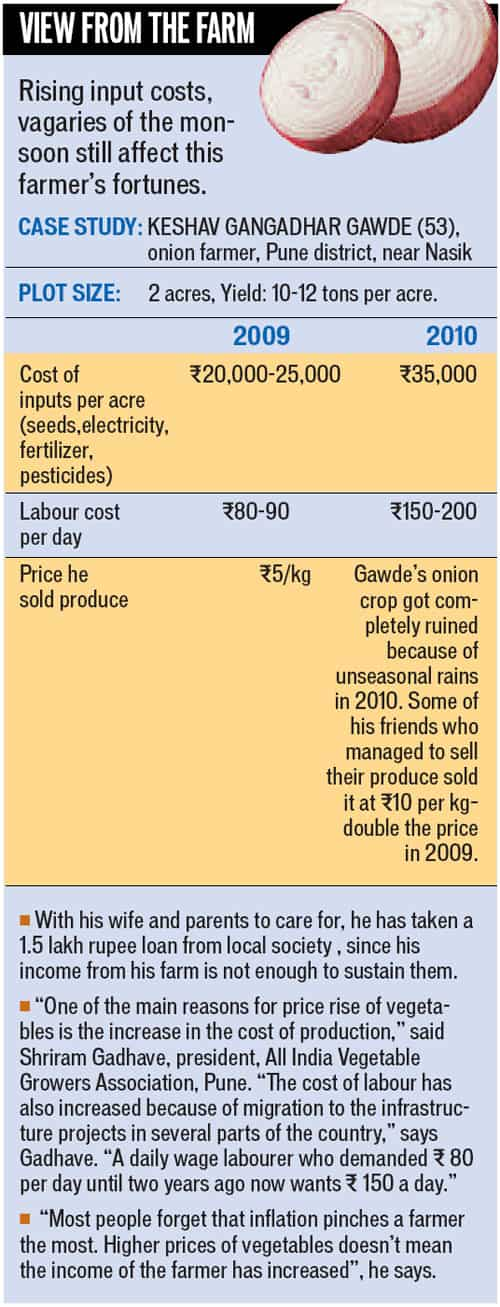

While the immediate reason for the spike in onion price was weather-related, policy oversight also played a role as the government allowed export of onion despite warnings of an imminent shortage due to unseasonal rains destroying the crop in India's onion belt near Nasik.

Many experts - including MS Swaminathan, agriculture scientist and father of India's green revolution - are perplexed by shoddy government policies.

"In a large country like India, some or the other place will see unseasonal rainfall - in Andhra, for example, there was unexpected heavy rainfall at the end of the rice season, but on the whole 2010 was not bad. We have to be prepared for such situations. If there were unseasonal rains - why were we at the same time exporting onions?" he asks.

"If the government is serious about tackling food inflation, it needs to work on understanding where the problem lies. Judging by the statements made by various economists working for the government, it's clear they don't have a clue," says Reetika Khera at the Delhi School of Economics. "It could be production, distribution, dietary diversification, hoarding, or all of these."

Many factors

Most economists agree that there is no one reason behind the recent surge in prices. From erratic and deficient rainfall to higher food demand of a prospering population, there many factors at work. "Rains are a factor, but not for all crops," says Ramesh Chand, director, National Centre for Agricultural Economics and Policy Research.

"Even if you take out the commodities which were affected by the rains, there is still high food inflation in the remaining ones," he adds.

Domestic food prices are increasingly getting linked to international prices as India's economy gets globalised. Between December 2008 and December 2010, the Food and Agriculture Organisation's (FAO) food price index rose 50%. The index measures prices of commodities traded in the global market, which are often influenced by speculation resulting from developments such as a bad summer in Russia and floods in Australia.

But to take refuge under global factors and say the government has no control over them, as UPA officials have often done, is bit of a stretch.

Because in India, "we have a series of tariffs and physical controls to dampen the effect of international price fluctuations," says Ashok Gulati, Asia head of the New York-based International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI).

Moreover, India is not a big importer of rice and wheat or fruits and vegetables. Gavin Wall, FAO's representative in India says, "The current food inflation has been primarily driven by domestic fruit, vegetable and milk prices."

Some like Planning Commission deputy chairman Montek Singh Ahluwalia would like to hold 'rising prosperity' responsible.

As rapid economic growth leaves Indians with more money, they tend to consume more fruits, eggs and milk. But Ashok Gulati qualifies. "The idea that increasing prosperity has led to higher inflation pressures on food grains is misleading. Between 1993-2004, as incomes increased, per capita cereal consumption increased only for the bottom 5% of income levels. Most of the pressure goes to fruits, vegetables and eggs and milk. However, this is a long term phenomenon. The kind of price rises we have seen in the last 2 months cannot be caused by a rise in overall prosperity," he says.

In some ways, this imbalance in growing demand and stagnant supply is also a result of myopic policies of the past.

Middlemen are also to be blamed for the ballooning food prices. "One of the major bottlenecks, especially for fruits and vegetables, is our mandi system. It benefits middlemen more than consumers or farmers," says Gulati. "The commissions are high, there is licensing, hurting free entry. Officially the commission is 6%, but unofficially it goes up to 10% for a 5-minute job."

That said, it's the rising cost production that stands out in contributing the most to the recent rise in food prices.

From electricity to pesticides and seeds, the farmer is paying a lot more to grow his crop than he did a few years ago. Thanks to the economic boom and programmes such as the NREGS, labour costs have risen sharply. The result: in the onion belt of Nasik, farmers spend 40% to 70% more on his crop than they did two years ago.

Simply put this means that high prices are here to stay, unless we invest in technology to improve productivity and reduce cost of production in the longer term. Deeper reforms in agriculture- from production to distribution, not just a tight monetary policy are required to cool inflation.

"Prices may well stabilise, but at a higher level of equilibrium," says Biraj Patnaik, Supreme Court Commissioner on the Right to Food. "There is no quick fix for this kind of inflation. We have not invested in agriculture since 1992. We need to think of agriculture in the long term - infrastructure, storage etc."

Until that happens, says Ramesh Chand, "we should all be prepared to pay more for food." That's not good news for Meerabai. Her dreams of saving enough so as to send her three daughters back home to school are long gone. "I've no idea how my children back home are doing without me."

The Hindustan Times' Tracking Hunger series is a nationwide effort to track, investigate and report all facets of the struggle to rid the nation of hunger and malnutrition.

Stay informed on Business News, TCS Q4 Results Live along with Gold Rates Today, India News and other related updates on Hindustan Times Website and APPs