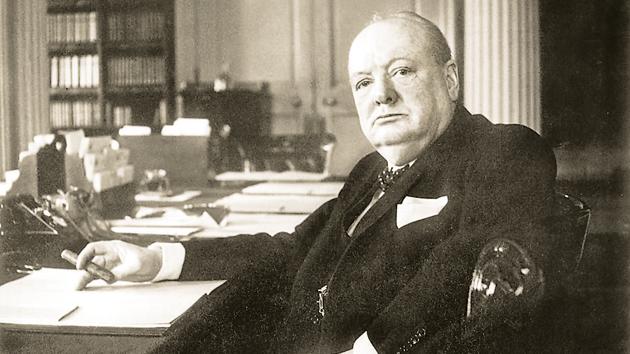

The two faces of Winston Churchill

He was an unapologetic imperialist, who believed that India could never become a nation, that Indians should remain forever under the British yoke.

Earlier this month, a flaming row broke out in Britain, when the Labour leader John McDonnell criticised Winston Churchill for having ordered troops to fire on striking workers in 1910. He was savagely denounced by his political opponents. The Tory grandee Sir Nicholas Soames, himself a grandson of Churchill, said “my grandfather’s reputation can withstand a publicity-seeking assault from a third-rate, Poundland Lenin. I don’t think it will shake the world.”

That may be true, in so far as Britain goes. There, Churchill is (rightly) venerated for having stood up to the Nazis when his party colleagues seemed unwilling to do so. A solitary death in police firing is seen as trifling as compared to saving his country during World War II. But what about assaults on Churchill’s reputation from other places, such as India? His distaste for Indians (“a beastly people with a beastly religion”), his venomous hatred for Gandhi, and his denial of food aid to the starving peasants of Bengal are well known. This column consolidates the case for the prosecution, by way of a document that I recently found in the archives.

This is a six page memorandum that Churchill prepared in September 1932 for the British Parliament’s Joint Committee on Indian Constitutional Reforms. Here he wrote that “the worst part of all the mischiefs which have arisen from the Round Table Conference and from the loose sayings of politicians, has been the omnipresent underlying suggestion that whatever is to be done now [in India] is but the forerunner, or as it were the earnest, of far more sweeping changes which are impending”.

In this note, Churchill set out to combat this mischief, to make it clear that in his eyes, at any rate, British rule in India must continue indefinitely into the future. He complained that “the term ‘Dominion Status’ has been used so loosely as to cause harmful misunderstandings”. Churchill wrote that it is “wrong for the high servants of the Crown, whether Ministers, Viceroys, or Governors, to use this phrase or to hold out hopes based upon it, unless they see their way to its practical realisation within some period of time to which living men can reasonably look forward. If they have ideas that India may become a self-governing dominion like Canada or Australia within one hundred or two hundred years, and that is all they mean by it, they ought not to use such a phrase without also explaining that it cannot be achieved in any period which men can foresee”.

Churchill further claimed that “India is not a country or a nation; it is rather a continent inhabited by many nations. The parallel to India is Europe. But Europe is not a political entity. It is a geographical abstraction. No one after centuries of progress can voice the opinion of Europe, or claim to speak in ‘her’ name. But the racial and religious divisions in India are more numerous and far more deep than those which rend Europe. Such unity and sentiment as exists in India arises entirely through the centralised British Government of India … . It seems to me therefore unhelpful … to imagine that any settlement on any subject can be come to by a bargain with India as a whole”.

Writing in 1932, Churchill thought India could never be an independent nation “in any period which men can foresee’. To see how truly reactionary he was in this regard, I shall contrast his views not with those of Indian nationalists, but with those held by his party colleague, Lord Irwin, a former Viceroy of India. In the same year, 1932, Irwin gave a lecture at the University of Toronto, where he spoke of how popular movements had recently arisen in Egypt, China, Persia, Afghanistan, and Japan, these “working to cast in firm shape the inspirations of nationalist enthusiasms”. Therefore, said Irwin, “by no human reckoning could India be expected to remain unstirred by the surrounding ferment, and we deceive ourselves unless we recognize that Indian nationalism is strong and will grow stronger”.

Irwin then came to the role of the pre-eminent Indian politician of the day. He acknowledged that “so far as any man can personify a movement so many-sided, Mr. Gandhi, blend of mystic and politician, has long stood as the symbol of the struggle for national autonomy”. The Mahatma, he said, “appeals to deep forces in Hinduism of which we [in the West] know little, and he leads his followers into realms of thought we can hardly follow”. He added that “by reason of Mr Gandhi’s devotion to ideals and readiness to impose and to accept any sacrifice” on himself in pursuit of the ideal of national freedom, “his power over his Hindu followers differs in kind from that of any other, and as often as he care to stir them, so often will vast numbers of them respond”.

This view of Gandhi was somewhat limited. While a Hindu in his personal beliefs, in his politics Gandhi strove to represent Indians of all regions and religions. But that apart, Irwin had a notably sympathetic approach to Indian claims and aspirations. He knew that Indian nationalism, already strong in 1932, would grow even stronger, and he was prepared to welcome this.

Whereas Winston Churchill was not. He was an unapologetic imperialist, who believed that India could never become a nation, that Indians should remain forever under the British yoke. On the question of Hitler and the Nazis, Churchill was absolutely right. On the question of Gandhi and India, he was wholly wrong. Defender of national freedom at home, upholder of racial oppression abroad — such were the paradoxical politics of Winston Churchill.

Ramachandra Guha is the author of Gandhi: The Years That Changed The World

The views expressed are personal