What does it take to win Assam? A fine balance between religion and language

If there is one state in India where migration is a big issue, it is Assam. There are multi-layered political fault lines in Assam, which encompass caste, religion, linguistic nationality, migration and deprivation

Assam is the only major Indian state which had a Congress government for three consecutive terms in the post-2000 period. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) led alliance first inflicted an upset in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections in the state and then captured power in 2016.

The BJP had the second-highest seat share to vote share ratio among major states in Assam (Bihar tops the list) in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections. In a first-past-the-post (FPTP) system, this ratio is a useful indicator of a party’s ability to convert popular support into seats.

Watch | ‘Confident of BJP’s win’: Assam CM; Congress asks to vote out ‘politics of hate’

Among the major states where the Congress contested on its own or as the senior alliance partner, it had a much better seat share to vote share ratio in Assam than places such as Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, where it actually defeated the BJP in assembly elections held in 2018.

Also Read | Barak Valley: Cong’s anti-CAA stance may hurt it; BJP’s worry is Assam Accord

These are not random statistics, and understanding their origins is crucial to understanding the multi-layered political fault lines in Assam, which encompass caste, religion, linguistic nationality, migration and deprivation. While the state’s politics is driven by many factors, the larger issue is the dynamic between language and religion.

Assam’s political geography has been shaped by historical migration

If there is one state in India where migration is a big issue, it is Assam. The state has seen two distinct waves of migrations. There are Bengalis, both Hindus and Muslims, who largely came from what was East Bengal before independence and is Bangladesh today. This migration existed in both the pre and post-independence period. Then there was large scale migration of what are today referred to as Tea and Ex-Tea Garden Tribes, who are recognized as Other Backward Classes by the Assam government. Even the government acknowledges that “economically, they are quite backward and (the) literacy level among these communities is extremely low”.

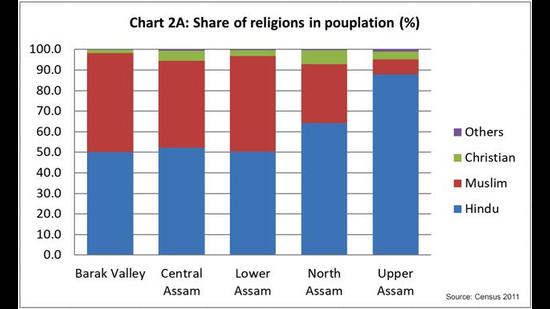

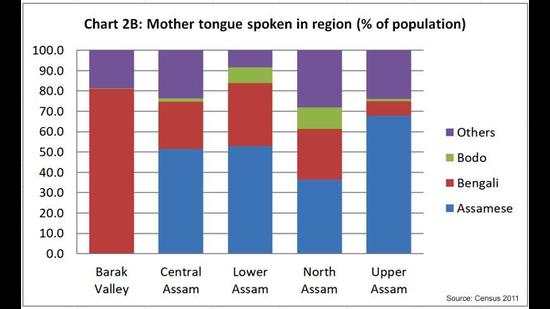

To be sure, Assam also has a large share of Scheduled Tribes (ST) in the population; they have always lived in the region and, culturally, are very different from the tea-tribes. These factors are best understood by looking at diversity across sub-regions in the state’s population by religion, language and social group. Assam is broadly classified into five sub-regions: Upper Assam, Lower Assam, North Assam, Central Assam and Barak Valley.

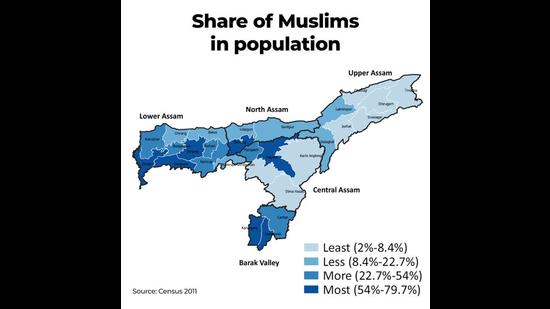

Muslims have a one-third share in the state’s population, but they are concentrated in a few pockets

After the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir was bifurcated into two union territories, Assam has the highest share of Muslims in the population among Indian states. This figure was 34.2% according to the 2011 census. As is often the case in India, the headline population share at the state level does not mean an equal distribution across districts. 15 out of the 27 districts in the state have a share of Muslims which is lower than the state average, whereas Muslims constitute a majority of the population in 9 districts. The Muslim dominated districts in the state border Bangladesh, which before independence, was just a neighbouring state.

For complete coverage of Assam assembly election, click here

It is this proximity to present day Bangladesh, and a history of political conflict – historians such as Amalendu Guha have described in detail how the issue dominated the Assam legislature even before independence – over migration of Bengali Muslim peasants to capture what were then Assam’s wastelands, which sowed the roots of an Assamese backlash against what were earlier Bengali migrants and are today seen as Bangladeshi migrants. Things only became worse when the Bengali Hindu elite tried to undermine the linguistic aspirations of the newly emerging Assamese elite, a contradiction which also existed both before and after independence.

Not all Bengalis in Assam are Muslims

The 2011 census puts the share of Bengali speakers – who reported the language as their mother tongue – at 28.9%. Once again, the headline number does not capture the intra-state diversity. While there is some overlap between the Bengali dominated and Muslim dominated districts, they are not a perfect match. Assam also has a large number of Bengali Hindus. For example, in the Barak valley region, which comprises three districts and 15 out of the 126 assembly constituencies (ACs) in the state, the share of Bengali speakers was 80.8%. Muslims have a population share of 48.1% in the sub-region. This means that there are a lot of Bengali Hindus in the state as well. Similarly, the state also has Muslims who speak Assamese. Because the census does not allow a religious segregation of languages spoken, it is difficult to arrive at official estimates of a religious-linguistic matrix for the state.

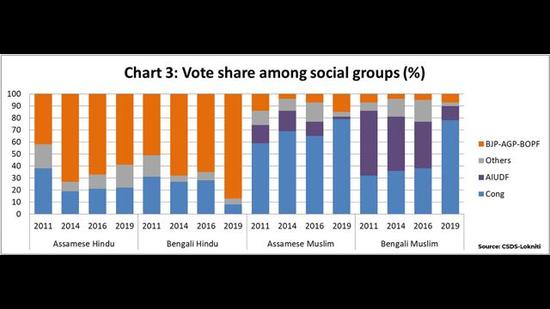

The intersection of linguistic and religious identity matters a lot in Assam politics

The BJP’s politics thrives on building a rainbow coalition of Hindus across India. While it has had success on this count in Assam (this is what explains the party’s current dominance in the state), it is still not as stable as it would like it to be. To be sure, this is not an easy task given the historical animosity between Assamese-speaking Hindus and Bengali-Hindus who are largely migrants. Data from the CSDS-Lokniti surveys shows that the BJP has consolidated almost the entire Bengali Hindu vote bank between 2011 and 2019. However, its support among Assamese Hindus has gone down after having peaked in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections. To be sure, a majority of the Assamese Hindus supported the BJP in the 2019 polls.

The Congress, when it won the 2011 elections, had a more broad-based support among the state. But Assamese speaking Muslims were its most loyal supporters. Its support among the Bengali speaking Muslims was significantly lower. The Bengali Muslim community in Assam has been known to be a supporter of the All-India United Democratic Front (AIUDF) led by Badruddin Ajmal; 20% of the AIUDF’s vote share and 31% of its seats were concentrated within the Barak Valley region in the state in the 2016 elections, when it recorded its best ever performance in terms of vote share in assembly elections, although the region only accounts for 12% of ACs in the state.

With the rise of the BJP, the Congress’s support among the Muslims has increased and also transcended the linguistic divide which existed earlier. It is this development which explains Ajmal’s accommodative posture towards the party in the current elections. With the Congress being seen as the biggest anti-BJP force in the state, AIUDF’s support base would have gravitated towards it, alliance or no alliance.

As is obvious from the numbers above, the Congress needs to increase its support among the Hindus, either Assamese or Bengali speaking, in order to recapture power in the state.

By making the anti-Citizenship (Amendment) Act plank, an important part of its election campaign, the Congress seems to have consciously decided to try and win back the Assamese speaking Hindus, a community it has had better support from compared to the Bengali Hindus. Because the CAA talks about retrospective grant of citizenship rights to Hindus from neighbouring Bangladesh, a section of the Assamese speaking population, is apprehensive about its de jure impact on the state’s demographic profile.

The BJP, on the other hand, is hoping to spoil the Congress’s effort by attacking the latter’s alliance with the AIUDF, a party which is seen to champion the interests of primarily Bengali speaking Muslims.