Here’s why India is struggling and failing to control tuberculosis

TB is continuing to devastate lives in India because of the government’s inability to regulate an exploitive private health sector, and to fill gaps in the supply of live-saving medicines.

“You have TB,” my general practitioner said. These three words changed my life,” writes Deepti Chavan in The BMJ, who was treated by private practitioners in Mumbai. A year into the treatment, she was told she had multi-drug resistant TB (MDR-TB) and needed surgery.

Charan was 16 when she first started coughing. It was in the middle of school exams. After months of incessant coughing, a chest x-ray confirmed TB.

It took six years of medicines, 400 injections, and two major surgeries to cure her.

Chavan’s treatment would have been more effective and less traumatic for her if her doctors had got a drug-susceptibility test done instead of simply changing prescription medicines, if they had listened when she said she had side effects, and if they had informed her about the options available in the public sector, where everyone diagnosed with TB is treated free under India’s directly-observed treatment short-course (DOTS).

That’s a lot of “ifs” for a disease that is curable and treated free in the public sector.

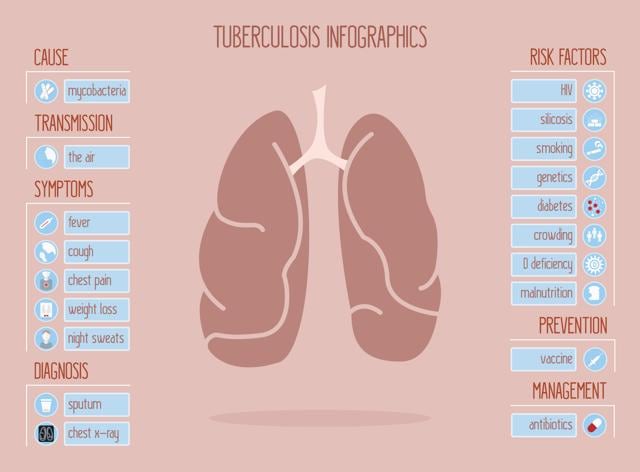

It partly explains why India accounts for 2.8 million of the 10.4 million new tuberculosis cases globally, according to the World Health Organisation Global TB Report 2016 which revised and raised its global estimates in 2016 after improved surveillance data from India registered a 34% spike in new cases.

Just six countries accounted for 60% of the world’s new TB cases — India, Indonesia, China, Nigeria, Pakistan and South Africa. Of these, people living with HIV accounting for 1.2 million (11%) of the new cases.

The spike in new cases is because India’s web-based notification system called e-Nikshay has made it easier for practitioners in the public and private sector to register cases, but recording data is not enough. It is how you use the data that matters most. Ensuring patients complete the full course of the treatment becomes mandatory to cure the disease.

And that’s where India’s public health programme to control TB is failing its people. TB is continuing to devastate lives because of the government’s inability to regulate an exploitive private health sector, and to fill gaps in the supply of live-saving medicines.

It’s failing because treatment is not just about writing prescriptions and giving away free medicines. It’s about curing a disease. It’s about talking to patients to make them understand why they must have the cocktail of highly toxic medicines that may make them feel sicker but will ultimately rid them of the pernicious infection.

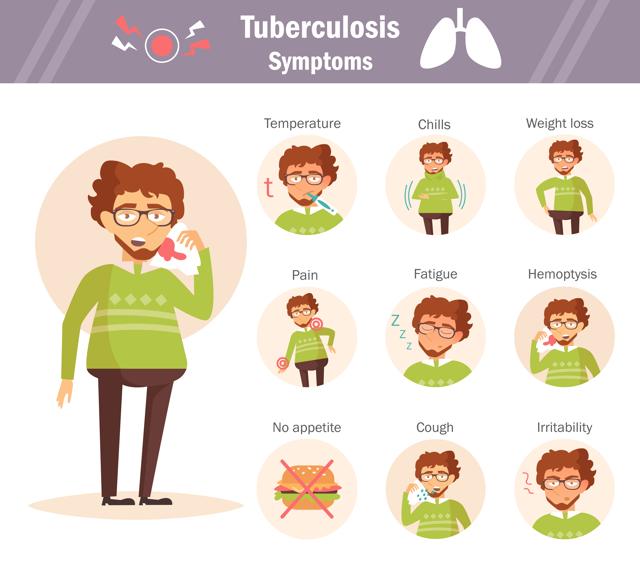

Several thousand TB patients across India stop treatment because their malnourished bodies cannot cope with the acute side effects, which range from loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, burning stomach to skin rash, jaundice and burning.

Not completing the full course of medication which takes at least six to eight months for uncomplicated TB leads to drug resistance, making the infection more difficult to treat. Stopping treatment midway is a major reason why around 3 lakh people in India die each year from this respiratory infection.

Growing drug resistance is slowing cure rates because the MDR-TB treatment success rate globally was an abysmal 52% in 2013. About 2.5% of all new TB cases in India are resistant to rifampicin, or to both rifampicin and isoniazid – the two most commonly used anti-TB drugs. At the end of 2015, India had 79,000 cases of drug-resistant TB, 11% more than in 2014. India, China and the Russian Federation accounted for 45% of the combined 5.8 lakh cases.

The private sector in India treats an estimated 2.2 million TB cases, estimated a 2016 study in The Lancet, which based its projections on data from the sale of drugs containing rifampicin, the main anti-TB drug. The study also said that the cases treated in the private sector in 2024 India could be anything between 1.19 million and 5.24 million.

India is a signatory to the WHO’s ‘The End TB Strategy’ that calls for a world free of tuberculosis, with measurable aims of a 50% and 75% reduction in incidence and deaths, respectively by 2025, and corresponding reductions of 90% and 95% by 2035. To meet these targets, India is adopting newer strategies, such as increasing rapid molecular diagnostics, Cartridge Based Nucleic Acid Amplification (CBNAAT) sites provide rapid decentralised diagnosis of MDR-TB, and use of bedaquiline, a new anti-TB drug through conditional access to treat drug-resistant TB.

Providing daily-dose medicines for the treatment of new drug-sensitive TB cases using fixed-dose combination in 104 districts in five states is also expected to improve compliance, as is prescribing fixed-dose combinations of first-line drugs according to the patient’s weight.

In 2015, 14,23,181 people registered for treatment, shows data from India’s annual status report TB India 2016. the data, however, does not mention the number of people cured. Until each patient is followed through, India’s TB control efforts will continue to flounder.

Follow @htlifeandstyle for more

Catch your daily dose of Fashion, Health, Festivals, Travel, Relationship, Recipe and all the other Latest Lifestyle News on Hindustan Times Website and APPs.