Ensuring safety of migrants key policy challenge for govt

A majority of the return migration will likely originate from districts in red zones (hotspots). Therefore, returnee migrants are at a higher risk of being carriers of infection.

On Labour Day, 38 days after a nationwide lockdown was announced, the first train ferrying migrants ran from Lingampally in Telangana to Hatia in Jharkhand. As the country trudges back to the new normal, a critical policy challenge will be to ensure the safety of the millions of migrants returning home. The preparation to safely transport migrants across the country will require data-driven decisions and an understanding of the arduous circumstances that await them and their families.

We already know that migrants will go back from urban industrial hubs to their homes in rural areas. In this article, we stitch together several different data sets to understand the characteristics of their home districts and some potential challenges that await them.

A majority of the return migration will likely originate from districts in red zones (hot spots). Therefore, returnee migrants are at a higher risk of being carriers of infection.

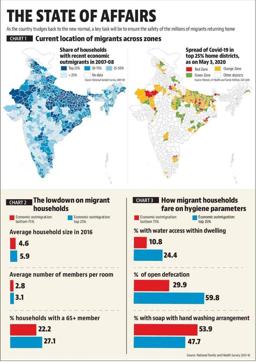

To approximate the districts migrants will potentially return to, we rely on the most recent data available from the National Sample Survey, 2007-08. We use data on both interstate seasonal migrants and recent migrants who moved for economic reasons.Since most of the return migration is expected to be geographically concentrated, we focus on the top 25% districts in the country that are most likely to receive migrants (Chart 1). These are the migrants’ home districts. These districts accounted for almost three-fourths of the migrant-sending households in the country. Over 78% of these districts were in six states: Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh. The characteristics of migrants’ home districts will predominately reflect the socioeconomic profile of these states.

More than 60% of the home districts are in red and orange zones, where the Covid-mitigation measures are still mostly in place . But a significant containment challenge remains for unaffected and recovered districts (green zones), which make up 39% of the home districts.

As migrants return from severely affected districts to their home districts concentrated in the northern and eastern parts of the country, practising strict self-isolation will be critical to limit the spread of the virus. Self-isolation will require the luxury of physical space for quarantine.

Isolating oneself may not be a trivial endeavour for returnee migrants: a typical household in the home districts has 5.9 members in contrast to 4.6 members in other districts.

Besides, more than three household members share a room, on average. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that they are also more likely to have a household member above the age of 65 years, and are therefore more susceptible to infection (Chart 2). In addition to congested homes, inadequate access to private water supply, sanitation, and hygiene infrastructure (WASH) – the first line of defence in the battle against Covid – could expose migrants, their families and communities to increased risk of infection and also make self-isolation challenging for returnee migrants. Indeed, this problem is severe in migrants’ home districts.

Only 24% of households in these districts had access to a private water source in 2016 (Chart 3). While access to a private source in these districts is still higher than other districts in the country, many still lack this necessity.

As many as 58% of the households in these districts practised open defecation in 2016. While the toilet coverage has increased vastly under Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, there is still a gap between access and usage.

The fact that less than half of the households in migrants’ home districts may be able to comply with recommended hand-washing with soap practices further reveals their vulnerability.

If these challenges translate into a rapid spread of infection, the consequences for both illness and livelihood management will be more precarious given that migrants’ home districts are poorer and less urban. Expectedly, their home districts also have a lower capacity to provide health care.

For instance, the average number of government district hospitals per 10,000 people in these districts is half that of the rest of the country.

Since the first lockdown announcement, stranded migrants across the country have been facing an uncertain future not only about their livelihood prospects but also about when they can see their families. As migrants prepare to return home, it is critical to acknowledge that they are likely going back to rural and more impoverished districts. That net emigration is occurring from urban and more industrialized red zone districts is, perhaps, not surprising. A large part of the net immigration will also be to the red and orange zone districts, that already have some containment measures in place. However, others will likely move back to places that have a low incidence of infection.

Here, preparations to protect these populations from the unfolding threat will be critical. While avoiding interpersonal contact is in any case challenging in India, data shows that it will be especially so for migrants and their families who lack adequate housing and WASH infrastructure.

Preparedness in the migrants’ home districts will be the key to restricting the risk of Covid-19 spread. Given that housing, water, or sanitation infrastructure cannot be improved overnight, the double whammy of moving to a more impoverished district and difficulty in practising social distancing highlights the need for other ingenious, quick, and contextually relevant solutions. For instance, wherever institutional quarantine is infeasible, instead of home quarantine, migrants can be asked to isolate themselves in schools or other public buildings in their home towns. Indeed, there is anecdotal evidence that returnee migrants are choosing to self-isolate for a couple of weeks before they meet their families. Furthermore, distribution of sanitiser bottles and face masks could be one quick way to respond to the inadequate water, sanitation, and hygiene infrastructure.

The vast institutional infrastructure of self-help groups can play a crucial role in managing Covid-19 response in rural India, by producing cloth masks, running community kitchens, and raising awareness, for instance. Above all, home districts will need to address these issues in a way that does not lead to stigmatisation of migrants.

Madhulika Khanna and Nishtha Kochhar are PhD candidates at Georgetown University. Esha Zaveri is an affiliated scholar at the Center on Food Security and Environment at Stanford

Get Current Updates on India News, Lok Sabha Election 2024 live, Infosys Q4 Results Live, Elections 2024, Election 2024 Date along with Latest News and Top Headlines from India and around the world.