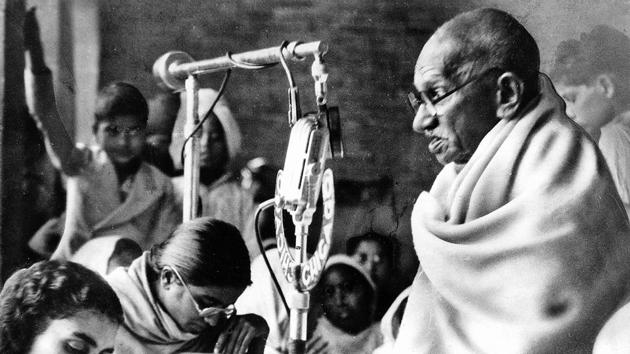

Gandhi’s last (and greatest) fast

In January 1948, Mahatma Gandhi sat on a fast for communal harmony – the last fast of his life. An exclusive extract from Ramachandra Guha’s new book on the leader, recalls that momentous time

It was not merely its status as the new nation’s capital that compelled Gandhi to stay on in Delhi in September 1947. He had an old and intimate connection with the city. He first visited it in 1915, to speak at St. Stephen’s College in Kashmiri Gate, where his friend C. F. Andrews had once taught. He came back often during the days of Khilafat and Non-co-operation. He knew and admired two great Delhi doctors; Ajmal Khan, trained in the Unani style, and M. A. Ansari, trained in modern medicine. Both were also patriots; both had been Presidents of the Congress. Gandhi was particularly close to Ansari, and was devastated by his death in 1936.

Gandhi knew, from personal experience, how Muslims had defined the city of Delhi, its architecture, its literature, its musical and its medical traditions. In a speech on 13th September, he remembered that when he first came here, in 1915, he ‘was told that Delhi was ruled not by the British but Hakim [Ajmal Khan] Saheb. … He was a Unani Hakim but had made considerable study of the Ayurvedic system. Thousands of Muslims and thousands of poor Hindus used to come to him for treatment’.

… Gandhi had praised his late friend Hakim Ajmal Khan for healing his Muslim and Hindu patients. He had come to Delhi now also as a healer, albeit of souls, seeking to reconcile Hindus and Muslims and help them rebuild their lives and their country. And not just in India, but in Pakistan too. As he told H. S. Suhrawardy, who came to see him on the 18th of September, ‘both Governments should make a clean breast of their mistakes and failures.’ Suhrawardy was on his way to Karachi; Gandhi told him to tell Jinnah ‘to face up to his own declaration respecting the minorities which were being honoured more in the breach than the observance.’

The same day, addressing a gathering of Hindus and Sikhs in Delhi, he urged them to ensure that Muslims lived, not as slaves, but as full and equal citizens of India. He hoped to soon leave for Pakistan, where, as he put it, ‘I shall not spare them. I shall die for the Hindus and the Sikhs there. I shall be really glad to die there’.

That trip to Pakistan would be contingent on the establishment of peace in India. There were millions of Muslims in the country; scattered across its villages, districts, and states. There were even some in his own village, who were ‘loyal to Sevagram, they would lay down their lives for it’. And yet some Hindus questioned the loyalty of all Muslims who had chosen to stay behind.

In one speech, Gandhi asked his audience: ‘Are you going to annihilate all the three-and-a-half or four crore Muslims? Or would you like to convert them to Hinduism? But even that would be a kind of annihilation. Supposing you were so pressurized, would you agree to become Muslims? … It is senseless to ask Muslims to accept Hinduism like this. … Am I going to save Hinduism with the help of such Hindus?’…

On October 2nd 1947, Gandhi turned seventy-eight. From the morning a stream of visitors came to wish him. They included his close lieutenants Nehru and Patel, now Prime Minister and Home Minister in the Government of India respectively. His devoted English disciple, Mira, had decorated the chair he customarily sat in with a Cross and the words Hé Ram, made of flowers.

Gandhi was not displeased to see his old friends and comrades. But his overall frame of mind was bleak.‘What sin have I committed’, he told Patel in Gujarati, ‘that He should have kept me alive to witness all these horrors?’ As he told the audience at that evening’s prayer meeting: ‘I am surprised and also ashamed that I am still alive. I am the same person whose word was honoured by the millions of the country. But today nobody listens to me. You want only the Hindus to remain in India and say that none else should be left behind. You may kill the Muslims today; but what will you do tomorrow? What will happen to the Parsis and the Christians and then to the British? After all, they are also Christians.’

… In the middle of November, the All India Congress Committee met in New Delhi. Addressing the delegates, Gandhi told them: ‘You represent the vast ocean of Indian humanity. You will not allow it to be said that the Congress consists of a handful of people who rule the country. At least I will not allow it.’

Gandhi’s talk at the AICC focused on religious harmony. ‘India does not belong to Hindus alone’, he insisted, ‘nor does Pakistan to Muslims’. Congressmen may ‘blame the Muslim League for what has happened and say that the two-nation theory is at the root of all this evil and that it was the Muslim League that sowed the seed of this poison; nevertheless I say that we would be betraying the Hindu religion if we did evil because others had done it.’ Gandhi reminded the delegates that ‘it is the basic creed of the Congress that India is the home of Muslims no less than of Hindus.’

That India did not belong to Hindus alone was also a recurrent theme in his prayer meetings. On 19th November, he spoke of how, in the old, historic, locality of Chandni Chowk, shop owners who were Muslim were being forcibly driven out. Two days later he reported that some 130 mosques in and around Delhi had been damaged or destroyed; such acts, he commented, ‘can only destroy [the Hindu] religion’.

Gandhi also spoke of the abduction of women by rioters. In West Punjab, Hindu and Sikh girls had been captured and often forcibly converted to Islam. On the Indian side of the border, Hindus and Sikhs had acted likewise with Muslim women.

Some of Gandhi’s disciples, such as Mridula Sarabhai and Rameshwari Nehru, were working on restoring these girls and women to their families. They estimated that the number of abducted women was close to forty thousand in all, a large, perhaps we should say alarming, figure. ‘We have become barbarous in our behaviour’, remarked Gandhi mournfully: ‘It is true of East Punjab as well as of West Punjab. It is meaningless to ask which of them is more barbaric. Barbarism has no degrees’.

… In Birla House, a new member had joined Gandhi’s entourage; a young English Quaker named Richard Symonds. He first met Gandhi with Horace Alexander in June 1942, and then caught up with him again in late 1945. In September 1947 Symonds returned to India to work among Partition refugees. In December he fell seriously ill with typhoid, and was admitted into a hospital, from where Gandhi had him removed to Birla House, where he spent several weeks recovering.

Every day, Gandhi would drop in to see the patient, and have a chat. When Symonds, agitated, spoke of Partition and its consequences, Gandhi instead turned the conversation to when he was studying law in London, the ‘only time he said, he was popular with the British’, because at dinner his fellow students could have his share of the wine alloted to their table. On Christmas Day, Gandhi had Symonds’ room decorated with streamers, and when he saw that Alexander had brought some celebratory sherry, remarked: ‘I see you are having high jinks. Well, what would not be right for me may be right for you’.

Decades later, reflecting on Gandhi’s kindness towards him, Symonds marvelled at how ‘this great man at a time of acute anxiety, pressure and sadness, had found it possible every day to nurse and chat and joke with a man of no importance’. In truth, Gandhi probably found the experience nourishing too; despite his hostility to British imperialism, he was enormously fond of the British, and in this time of tension and stress, conversations with a sensitive young Englishman would have been a relaxation. …

The public mood in Delhi remained angry, and soon rioting broke out once more in the city. Gandhi further postponed his plans to visit Punjab. This was just as well, for the trouble escalated. In Mehrauli, a village on the outskirts of Delhi, there was a celebrated Sufi shrine, visited by tens of thousands of people, including Hindus and Muslims. Now the Muslims whose families had tended the shrine for hundreds of years were hounded out by a Hindu mob.

On 12th January, Gandhi informed his prayer meeting that he was commencing a fast the next day. The recent riots had been contained by police and military action, but there was yet a ‘storm within the breast. It may burst forth any day’. So he had decided to go on a fast, which would end when he was ‘satisfied that there is a reunion of hearts of all communities brought about without any outside pressure, but from an awakened sense of duty’.

The Hindustan Times, edited by Gandhi’s son Devadas, reported that the decision to fast had come ‘as a complete surprise to his colleagues and the members of the Government’. Gandhi’s close associates ‘cannot conceal their anxiety’ at his decision, said the paper, as his health was still frail, after the fast in Calcutta. But Gandhi disregarded them, for ‘he had been very much affected by the all-round misery and chaos, thousands of refugees streaming to him with tragic tales.’

Meanwhile, in a private letter to his father, Devadas Gandhi wrote: ‘By your strenuous efforts [for communal harmony] lacs of lives were saved and lacs more would have been saved. But all of a sudden you lost patience. What you can achieve while living, you cannot achieve by dying’.

Gandhi would not be moved. On the morning of the 12th, he went to the Viceregal Palace to inform Mountbatten of his fast. Later, Nehru came to Birla House and sat with Gandhi for two hours. Although the stated reason for the fast was the deteriorating communal situation, it seems Gandhi was also upset with the Government’s decision to withold from Pakistan its share of the sterling balances owed by Britain to (undivided) India after the War. Because of Pakistan’s invasion of Kashmir, the Indian Government had delayed payment. But in Gandhi’s view of the world, financial debts to another person or entity, whether friend, enemy, or neither, had to be discharged immediately.

On the 13th, Gandhi had his usual morning meal of goat’s milk, boiled vegetables and fruit juice. Then he had a long conversation with Vallabhbhai Patel. The fast formally began at 11.15 am, after which some prayers were said.

… On the evening of the first day of his fast, Gandhi attended the daily prayer meeting and gave his address as usual. He spoke of, among other things, the perception that Indian Muslims trusted both him and Nehru, but not Patel. Gandhi thought this slightly unfair. ‘The Sardar is blunt of speech’, he remarked: ‘What he says sometimes sounds bitter. The fault is in his tongue’. He asked his Muslim friends to ‘bring to the Sardar’s notice any mistakes which in their opinion he commits’.

… On the evening of 14th January, a batch of angry men arrived on bicycles at Birla House and raised what were described as ‘communal and anti-Gandhi slogans’. Inside the house, speaking with Gandhi, were Patel, Azad, and Nehru. When the trio came out and heard the demonstrators say ‘Let Gandhi Die’, Nehru shouted: ‘How dare you say that. Come and kill me first’. At this the demonstrators dispersed, but no sooner had Nehru’s car sped away, than they reassembled. One of Gandhi’s doctors, Jivraj Mehta, tried to reason with them. They told him that the slogans were on behalf of the refugees who needed food, homes, clothes, and jobs.

At the prayer meeting that day, Gandhi spoke of reports of attacks on Sikhs and Hindus in Pakistan; if these ceased, they would have a beneficial effect on India. He then turned to his present ordeal.‘They tell me I am mad’, he said, ‘and have a habit of going on fast on the slightest pretext. But I am made that way’. When he was a boy growing up in Kathiawar, he had a dream ‘that if the Hindus, Sikhs, Parsis, Christians and Muslims could live in amity not only in Rajkot but in the whole of India, they would all have a very happy life. If the dream could be realized even now when I am an old man on the verge of death, my heart would dance’.

On the 15th, the third day of Gandhi’s fast, an American writer visiting India went to see him at Birla House. He saw him lying on a cot in the porch. Gandhi, reported this writer to his wife in New York, ‘was asleep, lying on his side in a embryo position. He was completely covered in a khaddar cloth, including his head, and framing his face. … An old man’s face and not attractive. In his sleep, he seemed to have lost control and it showed what he perhaps was feeling — suffering, intense suffering… . Somehow we never think of a Gandhi fast as a terrible physical experience. We think of it as a political manoeuvre, a strike, a gesture. But here it was in human terms, a process. Here was a 79 year old man deliberately killing himself in the most difficult and excruciating way.’

…At evening prayers on the 15th, Gandhi was visibly weak. From his bed, with a microphone next to him, he spoke in a barely audible voice for a minute. The rest of his speech, read out for him by Pyarelal, explained that his fast was on behalf of the minorities both in Pakistan and India. Conducted in the first instance ‘on behalf of the Muslim minority in the [Indian] Union’, it was ‘necessarily against the Hindus and Sikhs of the Union and [against] the Muslims of Pakistan’.

After the meeting, the crowd filed past him, one by one, bowing with folded hands, first the children, then the women, finally the men.

Meanwhile, news reached Birla House that the Government had agreed to pay the sterling balances owed to Pakistan, as their contribution ‘to the non-violent and noble effort made by Gandhiji, in accordance with the glorious traditions of this great country, for peace and goodwill’. The Government of India had bowed to Gandhi’s will; when would the city of Delhi do likewise?

… On Saturday the 17th, Gandhi entered the fifth day of his fast. His doctors issued a bulletin saying he was ‘definitely weaker and has begun to feel heavy in the head’. Besides, ‘the kidneys are not functioning well’.

Meeting Maulana Azad in the morning, Gandhi laid down seven conditions for breaking his fast. These were: 1. The annual fair (the Urs) at the Khwaja Bakhtiyar shrine at Mehrauli, due in nine days time, should take place peacefully; 2. The hundred odd mosques in Delhi converted into homes and temples should be restored to their original uses; 3. Muslims should be allowed to move freely around Old Delhi; 4. Non-Muslims should not object to Delhi Muslims returning to their homes from Pakistan; 5. Muslims should be allowed to travel without danger in trains; 6. There should be no economic boycott of Muslims; 7. Accommodation of Hindu refugees in Muslim areas should be done with the consent of those already in these localities.

Gandhi’s influence was finally permeating across the city of Delhi, ‘slowly but surely’. Two lakh people signed a peace pledge, which read: ‘We the Hindu, Sikh, Christian and other citizens of Delhi declare solemnly our conviction that Muslim citizens of the Indian Union should be as free as the rest of us to live in Delhi in peace and security and with self-respect and to work for the good and well-being of the Indian Union’.

… On the 17th evening, Gandhi somehow summoned the strength to speak at his prayer meeting. He thanked all those who had written or wired their good wishes (many from Pakistan). But he insisted that his fast was not ‘a political move in any sense of the term. It is in obedience to the peremptory call of conscience and duty’.

On the morning of the 18th of January, Hindu, Muslim and Sikh leaders met at Rajendra Prasad’s house. Here they signed a pledge assuring Gandhi that the seven conditions he had stipulated would be fully met. The Urs would be held at Mehrauli as usual, Muslims would be able to move freely all across Delhi, mosques taken away from Muslims would be returned to them, and so on. They all then trooped over to Birla House to present the undertaking to Gandhi. Reassured, and convinced, shortly after noon Gandhi accepted a glass of lime juice. As he did, reported the Hindustan Times, ‘the room rang with shouts of “Gandhiji-ki-jai”. A smile appeared on the face of Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru who had worn an anxious look all these days.’

Outside, the city of ‘Delhi was jubilant: its efforts to convince Gandhiji that the era of communal madness in the capital was over had succeeded.’ The news that the fast had been broken brought thousands of people to Birla House, despite it being a rainy day.

Over the past thirty-five years Gandhi had gone on fast every other year. The provocations had been various: sexual transgressions in the Ashram; violence committed in the name of nationalism; the oppression of ‘untouchables’; and, of course, the need for communal harmony. On the 16th of January, 1948, he wrote to a disciple now living in the Himalaya, who had been at his side in several previous fasts, that this latest yajna in Delhi was his ‘greatest fast’. And so it was.

[Excerpted with permission from Ramachandra Guha’s Gandhi: The Years That Changed The World 1914-1948, to be published next week by Penguin/Allen Lane.]

Get Current Updates on India News, Election 2024, Mukhtar Ansari Death News Live, Bihar Board 10th Result 2024 Live along with Latest News and Top Headlines from India and around the world.