Great harmoniser of India’s diversity, writes Ramachandra Guha

Mahatma in Delhi: MK Gandhi spoke of the dangers of Hindu majoritarianism on his first visit to Delhi in 1915 and he fasted to oppose communalism on his last visit, in 1947-48.

In the second week of April 1915, Mohandas Karamchand (not yet Mahatma) Gandhi visited Delhi for the first time. He had just come back to his homeland after two decades in South Africa, where he had made a name as a lawyer and an activist. His mentor, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, told Gandhi that for a full year he should travel across India, getting to know the country, before deciding what sort of public career he chose to have.

In Delhi, Gandhi stayed in the home of S.K. Rudra, Principal of St. Stephen’s College, to whom he had been introduced by his close friend, the Christian priest Charles Freer Andrews. Rudra asked him to speak to the students. So he did. As a report in the St. Stephen’s College Magazine (number 32, April 1915) has it, when the visitor entered the College Hall, he was greeted with “deafening and prolonged cheers”. Gandhi, speaking in Hindi, refused to offer the students advice on Indian politics, since Gokhale had told him not to speak on the subject until his year of travel had ended.

Gokhale himself had just recently passed away. Now, addressing an audience of Hindu and Muslim students in a Christian college, Gandhi focused on the religious pluralism of his mentor. Thus Gandhi described Gokhale to these students of Delhi as “a Hindu, but of the right type. A Hindu Sannyasi once came to him [Gokhale] and made a proposal to push the Hindu political cause in a way which would suppress the Mahommedan and he pressed his proposal with many specious religious reasons. Mr. Gokhale replied to this person in the following words: ‘If to be a Hindu I must do as you wish me to do, please publish it abroad that I am not a Hindu’. But Mr. Gokhale was a Hindu, and his religion was fearless.”

Some three decades after he made these remarks, Gandhi was killed in Delhi. Himself a Hindu, whose religion was (as it were) fearless, Gandhi was murdered because he absolutely refused to push the Hindu political cause in a way which would suppress the Mahommedan.

As is well known, shortly before he was assassinated on January 30, 1948, Gandhi had embarked on an epic fast for Hindu-Muslim unity. I will return to that fast, but before I do, I would like to speak of another, if now less known, fast for Hindu-Muslim harmony that Gandhi undertook in Delhi. In the summer of 1924, there were a series of religious riots across Northern India.

“Daily the gulf was widening,” commented one periodical published out of Kolkata: “Vernacular papers cropped up like mushrooms simply to indulge into the most unbridled license in ridiculing the religion and social customs of the opposite community, and they sold like hot cakes.”

The violence in the north deeply worried Gandhi, who had just come out of a long spell in prison. He travelled to Delhi, where, on September 17, he began a 21-day fast, which he described as a “prayer both to Hindus and Mussalmans, who have hitherto worked in unison, not to commit suicide”. “I am striving to become the best cement between the two communities,” said Gandhi, adding: “My longing is to be able to cement the two with my blood, if necessary. But, before I can do so, I must prove to the Mussalmans that I love them as well as I love the Hindus. My religion teaches me to love all equally.”

Gandhi broke his fast at 12.30 pm on October 9, 1924, when the great doctor and patriot, Dr. M. A. Ansari, handed him a glass of orange juice. Gandhi now asked his old friend from South Africa, Imam Abdul Kadir Bawazir, to read a prayer from the Koran. This was followed by a Christian hymn from C. F. Andrews, and a Hindu hymn from Anasuya Sarabhai.

To return now to Gandhi’s second and even greater fast for Hindu-Muslim harmony in Delhi conducted in January 1948. Following Independence and Partition, a wave of Hindu and Sikh refugees came to Delhi from West Pakistan. Their persecution at the hands of Pakistani Muslims had made them angry and embittered. They now sought revenge at the expense of the Muslims of India’s capital city. Fishing in these troubled waters were organisations such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh.

A Delhi police report dated October 24, 1947 observed: “According to the Sangh volunteers, the Muslims would quit India only when another movement for their total extermination similar to the one which was started in Delhi sometime back would take place. … They were waiting for the departure of Mahatma Gandhi from Delhi as they believed that so long as the Mahatma was in Delhi, they would not be able to precipitate their designs into action.”

The Mahatma knew of these designs, and thus absolutely refused to leave Delhi. Thousands of Muslims had already fled the capital; Gandhi was now determined to stop the exodus, and assure those who still remained that they would be safe and secure in a secular India. Through November and December he travelled to different parts of what is now known as the National Capital Region, reassuring Muslims, while at the same time urging Hindus and Sikhs not to take retributive action against Indians who had nothing to do with what was happening in Pakistan. “Are you going to annihilate all the three-and-a-half or four crore Muslims?” he asked his fellow Hindus: “Or would you like to convert them to Hinduism? But even that would be a kind of annihilation. … It is senseless to ask Muslims to accept Hinduism like this. … Am I going to save Hinduism with the help of such Hindus?”

The Mahatma was staying in the New Delhi home of his friend G. D. Birla, in the building now known as Gandhi Smriti. At the time, the High Commission of the United Kingdom was located on the same road. From his office window, the British High Commissioner observed who was going in and out of the place where Gandhi was staying. As he wrote in a report to London, “day in and day out, Muslims of all classes of society, many of whom had also suffered personal bereavements in the recent disturbances, came to invoke his [Gandhi’s] help. Normally too fearful even to leave their homes, they came to him because they had learned and believed that he had their interests at heart and was the only real force in the Indian Union capable of preserving them from destruction.”

On the January 13, 1948, an old and ailing man of 78 began a fast-unto-death to bring about Hindu-Muslim harmony. Speaking at a prayer meeting the next day, Gandhi recalled how, when he was a boy growing up in Kathiawar, he had a dream “that if the Hindus, Sikhs, Parsis, Christians and Muslims could live in amity not only in Rajkot but in the whole of India, they would all have a very happy life. If the dream could be realized even now when I am an old man on the verge of death, my heart would dance”.

On January 17, Gandhi entered the fifth day of his fast. The Hindustan Times reported that his moral example was taking effect, “slowly but surely”. Two lakh people now signed a peace pledge, which read: “We the Hindu, Sikh, Christian and other citizens of Delhi declare solemnly our conviction that Muslim citizens of the Indian Union should be as free as the rest of us to live in Delhi in peace and security and with self-respect and to work for the good and well-being of the Indian Union”.

Presented with this peace pledge, Gandhi ended his fast on the January 18. It took him a week to recover his strength and his health. On the 27th, he visited the tomb of the 13th century saint Qutubuddin Bakhtiyar in Mehrauli. A crowd in excess of ten thousand people had come to greet him. In a brief speech, Gandhi urged “the Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims who have come here with cleansed hearts to take a vow at this holy place that you will never allow strife to raise its head, but will live in amity, united as friends and brothers”.

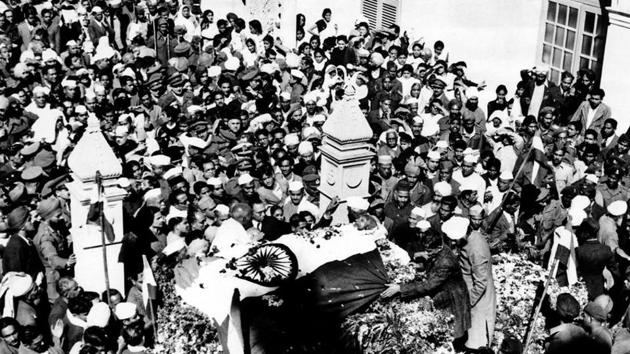

On January 30,Gandhi was murdered.

However, contrary to what Nathuram Godse and his supporters had expected, Gandhi’s exit did not create an open field for Hindu extremists to operate in. On the other hand, it horrified the majority of the country’s Hindus, who were shamed into atonement by the of their greatest compatriot.

Among those most shamed by Gandhi’s murder were Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel, Prime Minister and Home Minister respectively. As Nehru wrote to Patel, “with Bapu’s death, everything is changed and we have to face a different and more difficult world. The old controversies have ceased to have much significance and it seems to me that the urgent need of the hour is for all of us to function as closely and co-operatively as possible…” Patel, in reply, said he “fully and heartily reciprocate[d] the sentiments you have so feelingly expressed… [Bapu’s] death changes everything and the crisis that has overtaken us must awaken in us a fresh realisation of how much we have achieved together and the need for further joint efforts in our grief-stricken country’s interests”.

After Gandhi’s death, Nehru and Patel buried their personal differences to work together to build a united and secular India, in which Muslims would be as free as Hindus to live in peace, security, and self-respect.

It is striking that Gandhi spoke of the dangers of Hindu majoritarianism on his first visit to Delhi in 1915, and that he fasted to oppose Hindu majoritarianism on his last visit to Delhi, in 1947-8. Striking, and strikingly relevant too. For, as we mark the 72nd anniversary of his martyrdom, the strand in Gandhi’s many-sided life that speaks most urgently to us today is surely his absolute commitment to inter-faith harmony.

(Ramachandra Guha is the author of ‘Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World 1914-1948’)

Get Current Updates on India News, Lok Sabha Election 2024 live, Elections 2024, Election 2024 Date along with Latest News and Top Headlines from India and around the world.