Here’s why Marathas protest for reservation time and again

Marathas, who have historically dominated politics, are feeling threatened in the new economic order, where education and jobs matter more than farm incomes.

Maratha politics is on the boil in Maharashtra yet again. First, Devendra Fadnavis had to skip the customary worship performed by state’s chief minister at the Lord Vitthal temple due to threats by Maratha groups. Now, violence has engulfed Aurangabad town after a Maratha agitator demanding reservations committed suicide. What explains this intermittent flare-up among the Marathas in Maharashtra?

The short answer is growing socio-economic insecurity within the state’s dominant caste group. Marathas have a large share in the state’s population, they own large tracts of land and have enjoyed dominance in the realm of politics. But this traditional dominance is being threatened in the new economic order where educations and jobs matter more than farm incomes.

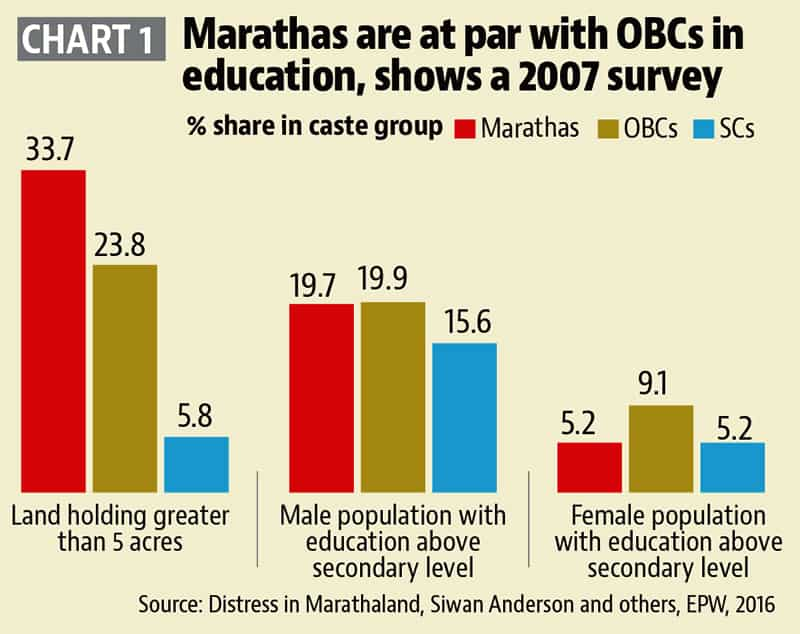

A 2016 Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) paper co-authored by Siwan Anderson from University of British Columbia and others shows that while Marathas were way ahead of Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and Scheduled Castes (SCs) in terms of ownership of large tracts of land, the advantage diminishes and even turns into a disadvantage when it comes to attainment of higher education.

Given the fact that there exists considerable heterogeneity among the Marathas, not all Maratha cultivators were better off than their OBC counterparts, the survey found. OBCs with large landownership reported much larger yields than Marathas with smaller tracts. With a deepening of the agrarian crisis, even large Maratha landowners are bound to have experienced a squeeze in their incomes.

These statistics were collected in a 2007 survey which was conducted among 9,000 households in 300 randomly selected villages of Maharashtra. More than 40% of the households covered in the survey were below the state poverty line.

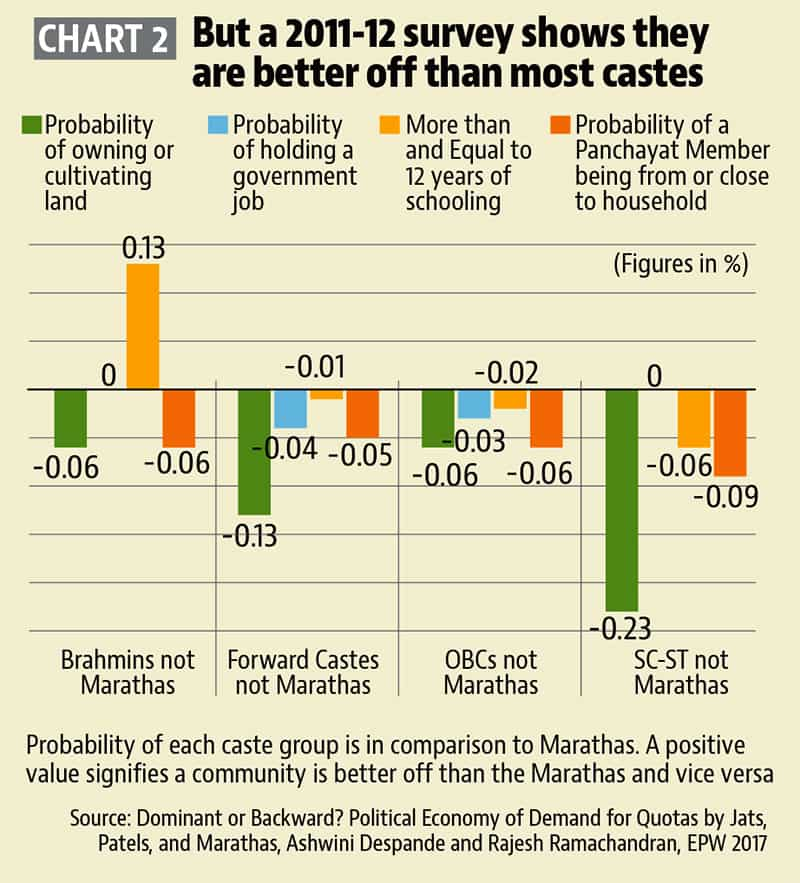

To be sure, statistical evidence from other surveys gives a different picture compared to Anderson’s findings. In a 2017 EPW paper, Ashwini Deshpande and Rajesh Ramachandran used data ( of 15,984 individuals) from the India Human Development Survey conducted in 2011-12 to show that the Marathas were actually better off than all caste groups excluding Brahmins not just in land endowments but also education and access to government jobs in Maharashtra.

The authors argue that rising discontent among dominant communities such as Marathas, Jats and Patidars is increasing due to the perception that real economic power is increasingly shifting from rural areas to big corporations, which are often backed by the state, while they themselves are ill-prepared to shift towards the urban and formal sector.

What explains the contradictory trends in the empirical findings of these two studies? Sampling-based errors in either of them could be one reason. Also, the first study’s results might have been influenced by the fact that it has a much greater share of poor households in its sample.

One aspect on which both these studies agree is the political mobilisation abilities of the Maratha community. Anderson’s survey found that even though Marathas had a share of 38% in the population, they filled 63% of the unreserved gram pradhan positions. Deshpande’s paper shows that Marathas have a greater probability of having a panchayat member who is close to or from their own households than all other caste groups. These statistics mean that there would be no dearth of people to undertake grass root mobilisation to run a community-based agitation. While Marathas have historically dominated politics at higher levels in the state, their clout might have weakened under the present Bharatiya Janata Party government, which has a Brahmin chief minister. It will be naïve to believe that opposition parties do not stand to gain from Maratha polarisation against the BJP, which is already staring at the possibility of having to fight the elections without an alliance with the Shiv Sena.

Another important, although in no way unique, factor which might be fuelling repeated protests by Marathas around the reservation issue is the larger scheme of how these take place in India. Pradeep Chhibber and others from University of California Berkeley had described it appropriately in June 2018 in these words: “The Indian state, no matter which party is in power, presents itself as mai-baap to its citizens. It, however, does not have the resources at its command to meet the demands raised by multiple and often competing groups. When these demands are not satisfied on favourable terms, it often takes organised action in the form of protests (and sometimes violence), for the state to respond. Over time this process has become ritualised into three distinct phases. A group’s demands are not heard or met. The group organises to protest, often violently. The state responds favourably.”

It needs to be remembered that the Marathas had actually successfully pressurised the state into granting them reservations before it was overturned by the judiciary.

Get Current Updates on India News along with Latest News and Top Headlines from India and around the world.