New battles of Bhima Koregaon: How a 200-year-old war inspires Dalits to fight caste system

The remote village of Bhima Koregaon in Maharashtra is where a handful of Dalit soldiers valiantly fought the Peshwa, their oppressors, 200 years ago. The battle continues to animate Dalit struggles and inspire generations in the war against caste. A ground report.

It is a little after 11 pm on New Year’s Eve when Anisha Savale gets off the tempo with her husband and three children. She has travelled for more than 400 kilometers in a packed vehicle, but as she rushes into a sea of humanity, her youngest in her arms, there is little sign of fatigue. Darkness hang over the fields on either bank of the Bhima river, save for a small clump of land dappled in light and the chatter of tens of thousands of people celebrating the bicentenary of the Bhima Koregaon war in a remote village in Maharashtra, roughly 40 kilometers from Pune.

The nine-acre plot is awash in blue flags and cries of ‘Jai Bhim’ rent the air as Savale pushes herself to the head of the queue – she wants to get her youngest to the 60-feet victory pillar, decked in yellow and orange garlands, before midnight. “I couldn’t come last year but couldn’t miss it this time. I have to show my children what their culture is and what they have to fight for,” says the 34-year-old.

Her son, dressed smartly in a white shirt and blue jeans with a prominent ‘Jai Bhim’ wristband on his right arm, tugs at her saree impatiently. “He wants to get a tattoo of Babasaheb,” she explains, but adds that she hasn’t made her mind up about it.

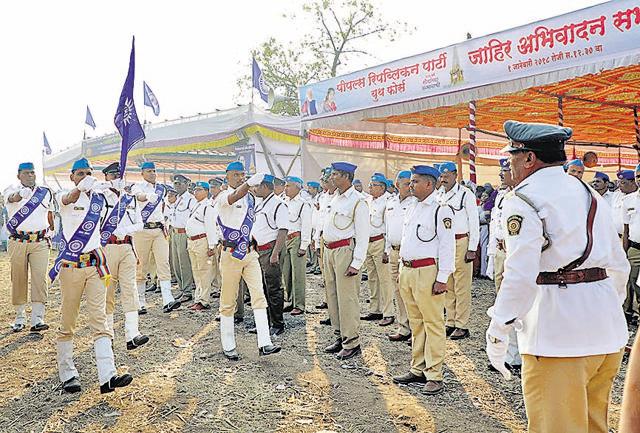

Around her, members of the Samata Sainik Dal, a volunteer organisation set up by BR Ambedkar in 1926, march up and down, readying themselves for a midnight tribute.

“We are not cowards, we don’t flee a battlefield…When our Babasaheb picked up the pen, look at the power he put in the Constitution,” the announcer from the stage booms to cheers.

A hush suddenly falls five minutes before the New Year as Buddhist monks serenely walk up to the makeshift enclosure around the “ranstambh” and begin chanting hymns – invoking Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism in 1956 to fight caste.

Savale stands on one of the makeshift bamboo-and-plywood bridges erected for the celebrations and mouths the words silently, her palms clasped in prayer.

Her son is looking at the plumage of fireworks that light up the winter sky to usher in the New Year, and pushes his way forward for a selfie with the plaque that commemorates the martyrs of the 1818 war on the British side. There are names of 22 Mahar soldiers, whose legendary tales of bravery now form the fount of Dalit pride today.

Next to him is 79-year-old Shanta Kamble, holding on to a handrail. She says she comes to the pillar every year, for at least 10 years. Why, I ask. She looks at me with pity. “You are young, you won’t understand. Do you think we would exist without this battle? We are here because of this. How can I not come?”

She spends the night in a tent, one of scores erected around the ground for people streaming in from across the country. There is excited chatter and songs sung in praise of Ambedkar, Jyotiba Phule and Shivaji. “It is like a pilgrimage for me but without religion, without garlands and worship. I cannot explain,” Savale says.

The celebrations go on through the night – people march in from faraway Karnataka, dressed in the elaborate yellow headgear that they believe the Mahar soldiers wore in the battle of 1818.

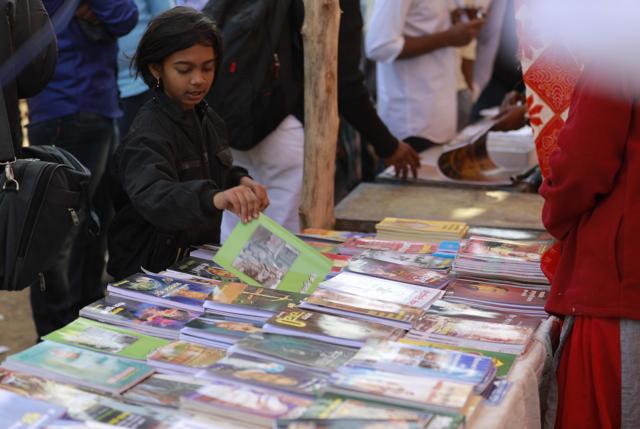

As the sun rises over the Bhima, people make a beeline for the freezing waters but only the bravest take the plunge. By 7am, the trickle of people turns into a flood and tempos, trucks, trawlers, and cars – all with blue flags fluttering – jostle for space. The SSD struggles to contain the swelling crowd that moves in great waves from the pillar to the shops behind that sell everything from anti-caste literature and pocket books on the Constitution and Buddhism, to sweatshirts with Ambedkar’s insignia, wristbands, busts and blue flags. In one corner of the middle lane is the tattoo stall.

“We have been coming here for 20 years. We sell books priced between 50 and 300 rupees,” says Sahebrao Patekar. The most popular of his wares are the books in Marathi detailing Ambedkar’s writings.

THE HISTORY

Bhima Koregaon grabbed the public imagination in 1927, when BR Ambedkar visited the spot and exhorted the Dalit population to remember their valiant history of ‘defeating’ the Peshwa.

India’s first law minister described in great detail the oppressive practices instituted by Brahmin rulers that forced every lower-caste person to carry a spittoon on their neck and a broom on the back, so that even their dust couldn’t pollute the dominant castes. Punishment for lower castes was often disproportionate and harsher than the upper castes, and Mahars, a caste Ambedkar belonged to, would ritually be sacrificed and buried to make the foundation of a building strong, explains Shradhha Kumbhojkar, a historian at Pune University.

“Phule and Ambedkar chronicled this and every conscious Dalit person has read them. The history of slavery, of oppression and ruthless death penalties has built this resistance,” she told me.

Recorded history of Bhima Koregoan is patchy, stitched together by historians from the correspondence of Captain FF Staunton with the East India Company and local oral histories.

But this much is certain: That Peshwa Bajirao II was already on the back foot on January 1, 1818. He had lost his seat of government in Pune’s Shaniwar Wada, from where the British flag had been unfurled in November 1817. With 20,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry, the Peshwa’s army vastly outnumbered Staunton’s 800-odd men, around 500 of who were Mahars. Both armies comprised a mix of soldiers from different castes and religions, and in the Peshwa’s case, 2,000-3,000 Arab mercenaries.

From here, the narratives diverge. Staunton’s journal records that the British forces took in heavy fire and attacks throughout the day on January 1, with one of their two guns exposed to the Peshwa’s army. There is no record of the losses on the Peshwa’s side but Staunton writes about a hurried dispatch to his superiors for more forces, while chronicling the poor state of his forces, the hunger and the fatigue.

But by afternoon of the second day, the Peshwa’s forces withdrew, allowing Staunton to pick up his wounded and return to the nearest camp.

“For the British, this was a big victory. The myth of dogged resistance started building in the first report sent to the East India Company,” says Kumbhojkar, quoting from records of the British Parliament and letters by then governor Mountstuart Elphinstone.

In the next six months, the Peshwa was vanquished, and banished to faraway Kanpur. The company showered accolades on Staunton and the other soldiers and in 1819 commissioned the memorial to the forces that ‘accomplished one of the proudest triumphs of the British army in the East”.

The Mahars too prospered, using the army’s patronage to escape the back-breaking violence and discrimination of the countryside, but not for long. The recruitment of lower castes stopped in 1892 after they were declared a non-martial race. This fomented a movement among the community that petitioned the British repeatedly. It is during this time, in 1910, that a British officer RA Lamb stumbled across the obelisk and told the Mahars that they could use the history of the Bhima Koregaon battle to win back favour with the British.

“The role of the military in the empowering of Mahars is great. Many of them tasted a better life working not just as soldiers but as butlers and tailors in the army. For the first time, they were addressed as human beings,” explains Kumbhojkar. Calling for the re-entry of Mahars in the army became a rallying point, and one of the leaders of that movement was Ambedkar’s father.

BR Ambedkar’s visit to Bhima Koregaon on January 1, 1927 was a watershed moment that pushed the then-forgotten war back into popular consciousness. He appealed to the British to reinstate the Mahars – which they briefly did during World War I – and even wrote a short treatise during the first Round Table Conference. The Mahar regiment was eventually raised in 1941, with Ambedkar a member of the Viceroy’s defence council.

Not everyone agrees. A section of Marathi literature throughout the 1960s and ’70s showed the Peshwa as the winner, most notably in the novel Mantravegla by Nagnath Inamdar (one of his books was adapted into the Bollywood film Bajirao Mastani).

“It is also important to note that the Peshwa’s army contained many different castes, and only a few Brahmins. The fight was not against Brahmins, it was against a regional power. The British created this other narrative for their advantage,” said Nand Kumar Nikam, former principal of the local Shirur College.

He finds echo in Anand Dave of the Akhil Bharatiya Brahmin Mahasangh, who says the battle was neither a caste fight nor were the Mahars victors. “The British wanted to defeat Hindu kings. What did the British give the Mahars afterwards? The bicentennial is a mark of anti-Brahmin sentiment.”

Kumbhojkar agrees there is a degree of myth involved but doesn’t see the harm, or the reason for outrage. “Every identity or community has its own myths. Dalits were creating an alternative to Hinduism through culture and Bhima Koregaon became a rallying point. There are layers of memories associated with the place.”

Conversations with Dalit leaders and organisers also dispel the notion that they are unaware of the contradictions in the narrative. “We know that the Mahars didn’t fight alone. But in defeating the Peshwa, the non-Brahmins won. We are told our history isn’t glorious but these soldiers are symbols of the first fight against anti-caste, they are a symbol for future generations,” says Keshav Waghmare, a Pune-based activist and one of the organisers of the bicentennial celebrations.

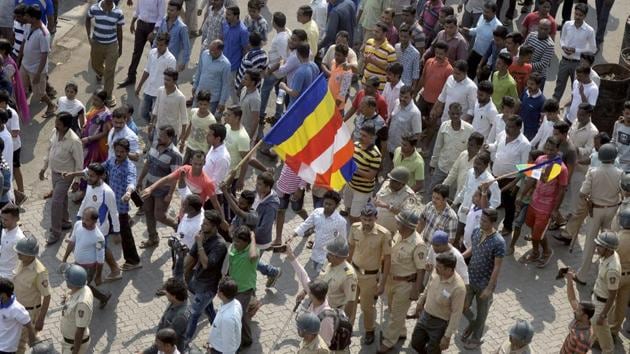

THE UNREST

Trouble started brewing on December 29 when unidentified men desecrated a little-known cemetery in Vadhu Budruk, less than five kilometers from Bhima Koregaon.

The cemetery was of a 17th century peasant from the Mahar caste, Govind Ganapat Gaikwad, who gave a funeral to Shivaji’s son Shambhaji, who was killed by Aurangzeb in 1689. Many historians believe that at a time when the local population was terrified of the Mughals and refused to cremate Shambhaji, Gaikwad stitched together his remains and gave him an honourable funeral.

This is an important moment in the anti-caste history because many thinkers believe Shivaji was a Shudra king who was opposed to Brahmins, though, his ashtapradhan (council of eight most important ministers) comprised mostly of Brahmins. In Bhima Koregaon itself, for example, a statue of Ambedkar faces another of Shivaji.

But a competing narrative is also afoot, helmed by hardline Hindu leaders such as Sambhaji Bhide and Milind Ekbote who are both accused of fomenting the violence near Bhima Koregaon that killed one person.

Sachin Garud, a professor at Islampur College in Sangli district, told me both these leaders work mainly in that district to peddle a narrative directly contrary to the version Dalit and Bahujan thinkers hold. “They say that Shivaji was a protector of Brahmins and that he was the raja of all Hindus. They say Shivaji was a proponent of caste and varnashrama,” he says.

In this backdrop, when Gaikwad’s memorial was damaged, it triggered tensions in the area, and resulted in an FIR against 49 villagers, including the chief, under the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe Prevention of Atrocities Act. It is from Vadhu Budruk again that the violence on January 1 began.

This cycle of violence might have opened a chasm between Dalits and a section of the Maratha caste that Shailendra Kharat, a professor of Political Science at Pune University, believes must be seen in light of growing right-wing influence in the state.

The Marathas and upper castes first clashed with Dalits in 1978, during a movement to change the name of Marathwada University in Aurangabad to BR Ambedkar University. The icon’s name was added after 16 years of protests that saw numerous atrocities on Dalits.

Simmering tensions between the two communities spilled out onto the streets last year after a gang-rape case in Kopardi, where Dalit men raped a Maratha woman. The case triggered a huge churning as hundreds of thousands of Marathas took out silent marches across Maharashtra. In September, three Dalit men were sentenced to death.

But another murder, that of a 17-year-old Dalit man for allegedly falling in love with an upper-caste woman, in Ahmednagar district, remained under the radar. In November, all accused in the case were acquitted for want of evidence.

“This generated tremendous anger among Dalits across Maharashtra. Not only was the boy killed but the killers let off. This sent out a message that Dalits couldn’t even fall in love,” said Sudhir Dhawale, an activist.

Kharat believes the root of these tensions lies in a persistent agrarian crisis and falling rural wages among the Marathas that have been aggravated by fragmentation of land holdings.

“The ascendance of Dalits, especially neo-Buddhists and Mahars, and their material dominance was met with hostility, especially as the material dominance of the Marathas waned in the ’90s,” argued Pune-based political scientist Rajeshwari Deshpande.

These shifting dynamics have also undermined another 100-year-old movement, called Brahmantar, that sought to bring all non-Brahmin castes under one broad Bahujan fold, says academic Suhas Palshikar. “The 2014 elections was the loss of hegemony of Marathas as the Brahmins felt more encouraged by the current dispensation,” he told me. At the same time, many Maratha groups have backed the Dalit protests across the state and local Marathas in Bhima Koregaon have come together with Dalit people to protest against the January 1 violence.

THE FUTURE

In the chaos of the past week, the one clear narrative was that of the educated Dalit person– mobile, articulate and proud of their ancestry and history. In the shadow of the obelisk on January 1 stood a group of seven young men who had spent New Year’s Eve in a bus from Belgaum in Karnataka, and raised slogans in praise of Buddhism, Phule and Ambedkar.

All were Dalit and said they were facing pervasive but intangible discrimination in their university – and were at Bhima Koregaon to gain strength for a fight that was to last for the rest of their academic careers. The group’s leader, a 23-year-old man in a suit named Yuvaraj Byale, appeared determined for a struggle.

His resolve found echo in the local village chief’s husband, Babusaheb Bhalerao. “We get strength from this monument – that everyone comes here,” he tells me. The event itself is funded by the community and is hosted by a committee of local villagers.

A little distance away in the rank and files of the SSD stood a 70-year-old woman, Nanda Kamble, and a 10-year-old boy, Adish Ingle. When asked why they joined an organisation that needs them to stand in the sun for long hours, manage crowds and take orders, their answers were almost identical: “We heard of Babasaheb and want to follow in his path.”

By now it is almost noon and time for Savale to leave but her son is still adamant about that tattoo. In her admonishment, she holds out a promise. “Read the books I have bought you about Babasaheb. I will quiz you and if you pass, next year I may let you get a tattoo,” she tells him. He seems content with the challenge as they climb into their tempo.

Get Current Updates on India News, Lok Sabha Election 2024 Live, Election 2024 along with Latest News and Top Headlines from India and around the world.