The new Dalit movement: Assertive, inclusive and beyond party politics

Caste prejudice is alive and kicking in India. But there is also a new Dalit movement - aware, assertive, self-critical, connected, inclusive, and beyond party politics

If geography determined power, Ambedkar Hostel in Lucknow’s Hazratganj would rank high in the matrix. Walk up to the terrace and you look out to UP’s Vidhan Sabha. Look down and you see the BJP state head office. And next door, a new CM secretariat is under construction.

Inside the Ambedkar hostel live SC and ST scholars of the Ambedkar University. They are surrounded by power. But they know it is a long way before they can exercise meaningful power.

Caste atrocities remain an everyday reality for millions. Dalits strongly feel that a new ‘sophisticated architecture’ of inequality is also in place. They remain under-represented in public positions. But it is not just a tale of victimhood. Dalits today are more organised and connected. They see themselves as a part of an assertive movement of social justice. They have sympathy for Dalit parties, but criticise the failures. They worry caste is getting reinforced, rather than annihilated – the ultimate vision of their icon BR Ambedkar.

HT explored the nature of discrimination and the current moment in Dalit assertion.

Read: Rohith Vemula: An unfinished portrait

Persistent discrimination

Ajay Kumar Rawat is sitting in his second floor room in the Ambedkar Hostel.

An Ambedkar picture is on the wall of his room; stacks of old Hindi newspapers are piled up; two laptops are strewn on the bed.

From a village in Unnao, Rawat has come a long way. He recently finished his PhD on contemporary Dalit movement in UP. “Twenty years ago, my teacher – a Tiwari – in the village used to mock us and say even if three generations of your family come together, you will not be able to study...I credit the state for this hostel room, for a fellowship, for creating a public university which enabled me to finish a PhD.”

Rawat is quick to underscore that that does little to compensate for the persistent discrimination. The National Crime Records Bureau data shows that the number of incidents of atrocities against Scheduled Castes increased from 39,408 in 2013 to over 47,000 in 2014. In UP, there were 5,784 incidents in 2012, 6,617 incidents in 2013, and 7,577 incidents in 2014.

Every day reports are tucked away in newspaper briefs – Dalit man shot for fetching water from a government tubewell in UP; Dalit girl assaulted in Chhattisgarh; Dalit killed over land dispute in Chhattisgarh; Dalit woman gang-raped in MP; Dalits face social boycott in Gujarat. Sarita, a student at the Ambedkar University in Mhow, said she felt the era of discrimination was over, until she began her academic research. “I did my fieldwork and across villages in MP’s Ratlam found persistent untouchability.”

The statistics do not capture the more insidious forms of prejudice – separate plates at a wedding; the decision not to rent out a house as soon as the tenant is found to be a Dalit; the quiet whispers in offices that someone has come from ‘quota’; the insistence that one’s son or daughter cannot marry ‘below’ caste; the gang-up against a Dalit student in a hostel and caste-based ragging.

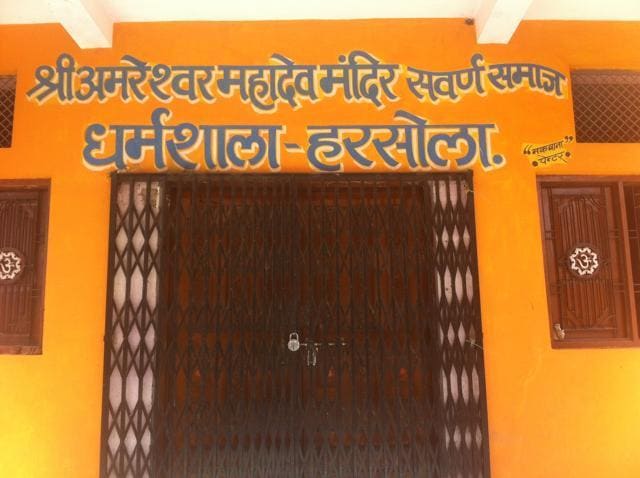

A few miles from Ambedkar’s birthplace in Mhow, there exist separate crematoriums for Dalits and non-Dalits in Harsaula village. Attached to the crematorium is a dharamshala which proudly announces itself to be that of ‘savarna samaj’. Caste is alive and kicking in India.

Institutionalising inequality

But it is the new forms of inequality – for instance, in access to quality education – which worry younger Dalits more.

In Harsaula, Vishnu Malviya, a Dalit politician, looked back at his school years. “I went to the government school here, along with children of all other castes. Today, kids of general castes go to private schools; it is mostly Dalit children who go to government school. The quality has dipped and we suffer from disadvantage right from this stage.”

Lucknow’s prominent Dalit activist, Ram Kumar, agreed. “Since children of decision makers don’t use public education, they do little to improve it. You are depriving Dalits of skills and education to compete at this stage itself.” He argues that in the old days, upper castes used the stick and law to prevent others from getting educated. “Now it is a more sophisticated architecture.”

Affirmative action has created a Dalit middle class. But those who have availed this right have their own stories to tell. A Dalit police official in an eastern UP district told HT there are usually two responses when his colleagues discover his caste identity. “First they think this guy has come from a quota, and so must be bad at his job. And then if proven wrong, they think this guy has come from the quota, but is still good. The first response shows contempt; the second is patronising.”

Representation remains elusive in key spheres. Take the Allahabad High Court, the centre of the city’s life. Advocates Satyaveer Singh and Suresh Chaudhary prefer the term Scheduled Castes to Dalits. Doing a rough back-of-the-envelope calculation, Chaudhary said, “There are only 300 or so SC lawyers out of the 10,000 lawyers in the Allahabad court. There is not a single designated senior advocate. And there is one Dalit judge in the court.” Singh adds, “When there is greater representation, there is greater legitimacy of the court.”

Read: Good Shepherd: Dalit thinker Kancha Ilaiah on name, caste

Assertive and organised

Why has the number of reported incidents of atrocities increased? Why is there an air of conflict around caste issues?

Activist Ram Kumar has a one-word explanation: “Assertion. In my father’s generation, if a Pandit came along, he would sit on the chair, and the rest would sit on the floor. And now, if a pandit comes, he can sit with us, or can stand and we keep sitting.”

Social hierarchy is challenged through these everyday acts. Many ‘upper castes’ cannot come to terms with this change. They want an older order, which provokes resistance.

Back at the Ambedkar Hostel, Ajay Rawat speaks of a new Dalit movement.

The spontaneous mobilisation after Rohith Vemula’s suicide across the country was one example. “Through social media, we reached Rohith. And Rohith reached us even after his death. Today, if there is a caste atrocity in Rajasthan, a Dalit in Lucknow can go to the Ambedkar statue, and protest with a banner and a flag.” Dalit students feel empowered with access to immediate information, and have tools to organise.

And they place their struggle in the wider battle of social justice. “We have to ally with backwards, Muslims, and even the poor of upper castes. They need to shed their superiority and we need to shed our inferiority,” says Rawat.

The economic shift has also opened doors. Chandrabhan Prasad, a key Dalit thinker, has argued that English language, urbanisation and capitalism will decrease the salience of caste. A new generation of Dalit entrepreneurs has risen. Others in the movement see it as positive, but then question the exclusionary and unrepresentative nature of the private sector. They also believe that this cannot be a substitute for state welfare and social reform.

Read: Death as a Dalit: What Rohith Vemula’s suicide tells about India

The elusive dream

Political power has helped, but younger Dalits are clear this is one part of a much wider movement.

Lavlesh Kumar, a PhD scholar in environmental law, hailed BSP for generating awareness among Dalits and empowering them. When Mayawati is in power, Dalits have the confidence to go to a thana to register their FIR. State resources are invested for community welfare.

But he also saw it as another political party, no longer a social movement. “Land is central to the Dalit issue. Our slogan was jo zameen sarkari hai, woh hamari hai – government land is our land. But BSP does not focus on land and economic justice.”

Mayawati is also seen as too silent given the contemporary nature of democratic discourse. “The party must engage in everyday debates. The older generation of committed cadres is no longer there, and we don’t see mobilisation on issues,” says activist Ram Kumar, who is a critical sympathiser. In that sense, Dalit society is ahead of Dalit politics.

What perturbs this generation of informed and aware Dalits most, though, is the increasing salience of caste in politics and society. “From selection of party office bearers to distribution of tickets, caste is central to politics,” says lawyer Suresh Chaudhary. In such a landscape, it is inevitable that Dalits – who have been discriminated on identity lines – would mobilise on same lines too. Many have hailed it as deepening of Indian democracy.

But while it empowers Dalits, it also reinforces caste identities. When I asked Brajesh, a Dalit scholar in Allahabad University, whether the solution is using caste to get to power or the end of caste, he responded, “The goal has to be the end of caste.” That goal – Babasaheb’s dream – remains elusive.

Get Current Updates on India News, Lok Sabha Election 2024 live, Elections 2024, Election 2024 Date along with Latest News and Top Headlines from India and around the world.